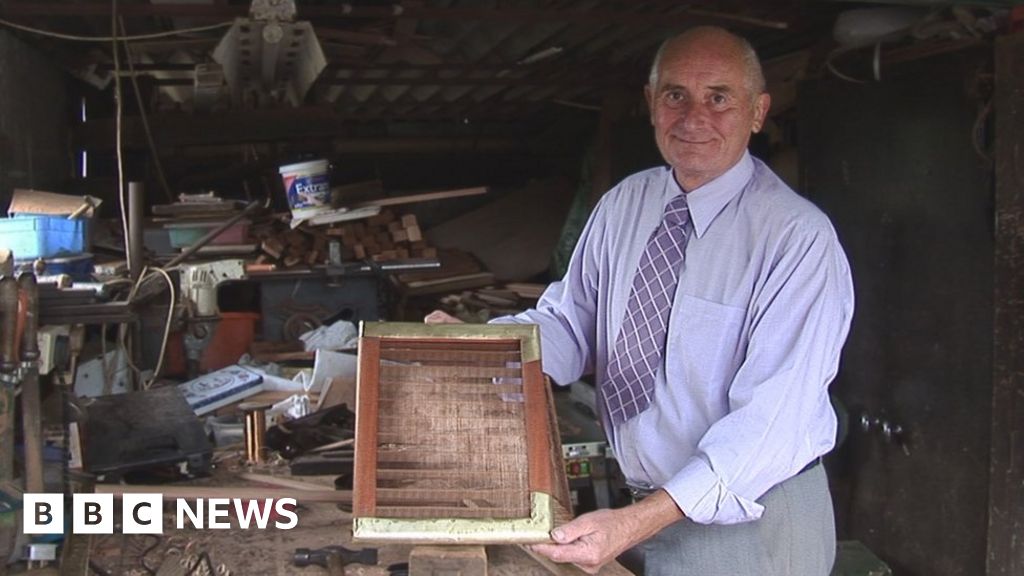

The death of a master craftsman in Kent in 2017 marked the end of an era. Not only was Ron Macdonald regarded internationally as a leader in his field, he was also the last member of his profession in the UK.

Mould and deckle-making - the manufacture of mahogany frames for hand-making paper - is still practised by his former apprentice, Serge Pirard, in Belgium. But in the UK the craft has joined the other traditional skills now officially classified by the Heritage Crafts Association (HCA) as "extinct". In recent years, cricket ball-making, gold beating and lacrosse stick-making have also ceased, with manufacture moving overseas or dying out completely.

More than 100 other weird and wonderful trades are considered at risk or even "critically endangered", according to the HCA, which supports craftspeople through fundraising and lobbying policymakers.

Withy pot-making

Withy pot-making classified as "critically endangered". As crab fishers began swapping traditional willow fishing pots for modern wire and plastic traps in the last century, the tradition diminished.

Withy pots have featured in paintings dating from 400 years ago but are thought to have been made long before that. Manufacture would have been a group activity by fishers along the coasts of the Isle of Wight, Dorset, Devon, Cornwall, south Wales and south and west Ireland.

The HCA estimates the number of professional withy pot-makers is now in single figures and those who remain use it as a sideline to their main income.

Artist and basket weaver Sue Morgan learned the skill in the 1990s from a retired fisherman in her community of Hope Cove in Torquay, Devon. She continues to pass on her knowledge through courses - although coronavirus has forced her to put those on hold.

"I became aware that this traditional style of small boat fishing had changed drastically through the '70s and '80s," she said, "and that old skills were rapidly disappearing. We have still got a course booked in for October which we hope will go ahead.

"It's very isolating doing craft by yourself so the network is quite important psychologically as a support and for information."

Orrery-making

It wasn't until mechanical engineer Derek Staines retired in 2004 that he made his first orrery - a mechanical model of the solar system. Within 10 years, what started as a hobby became an occupation. His son Timothy, also an engineer, is now believed to be the only full-time professional orrery-maker left in the UK, with his father now working only part-time.

A small orrery takes about a month to make and Norfolk-based Staines and Son would normally ship between six and 10 each year to customers all over the world.

One of the first known orreries is the Antikythera mechanism, from between 150BC and 100BC, which was discovered in 1900 in a wreck off the Greek island of that name. The first modern orrery was built by clockmakers George Graham and Thomas Tompion in the early 1700s.

Orrery-making has "seen a renaissance in recent years" and, although orders temporarily dried up during the recent lockdown, Timothy Staines says they are picking up.

"For me it has just been a blip," he said. "I had customers ask me to delay their orders but it's allowed me to develop new ideas and experiment and it's given me more time to put into the designs I already have. I certainly feel a responsibility to promote the craft myself and show how accessible and enjoyable it can be."

Clay pipe-making

Clay pipes have been used in the British Isles since the 1500s, following the arrival of tobacco in Europe. As the popularity of smoking grew, so did the number of manufacturers. Now, there are thought to be only three full-time clay pipe makers in the UK. Clients include filmmakers, re-enactment groups, smokers and collectors.

The original iron and brass moulds have become almost unobtainable - the majority are now in museums - leading some craftspeople to adapt their methods. One such maker is ceramic artist Heather Coleman, from Exeter, who makes the pipes using plaster moulds.

Each hand-finished piece can take between half-an-hour and several days to complete, depending on its complexity.

"The traditional methods are still used by my friend Rex Key," Ms Coleman said, "using original tools with iron moulds. I taught myself to make my own tools based on older methods but with modern materials. I do not teach people fine details of my ways because that would be preserving a 21st Century version of an old craft but I have advised people all over the world."

Arrow-making

Former music teacher Will Sherman is one of just a handful of professional arrowsmiths in the UK, making medieval replicas of historical artefacts in his forge in Avon, near the Hampshire-Dorset border. He took up the craft nine years ago, building a forge in his back garden using a steel sink and bellows made from pallet wood and sofa leather.

Today, his arrows, which have been developed using extensive historical research, are popular with archery enthusiasts around the world and can also be seen in museums.

He also passes on his skills through workshops in the New Forest, although these have been paused due to coronavirus. The HCA's Red List classifies arrow-making as an "endangered" craft, rather than "critically endangered". There are thought to be at least five full-time arrowsmiths, with half-a-dozen or more working as a sideline to their main income.

With its origins in the Iron Age, arrow-making is one of the oldest known crafts. It reached its peak during medieval times when the bow and arrow was the main weapon of war.

Although an arrowhead can take just five minutes to make, the rest of an arrow can take hours - from splitting the timber for the shaft and working it into a straight, tapered barrel, to stripping goose feathers and binding them with silk into handmade glues.

"Although I'm not a master arrowsmith yet, there are a few superb blacksmiths working today who do hold that title," Mr Sherman said. "It's something that takes decades to achieve and requires a complete understanding of the intricacies of metallurgy, archaeology and the craft itself.

"What I've found in this career is that you never stop learning.

"Sometimes I'll go into a museum and handle a particular arrowhead tucked away in a box somewhere in a storeroom and realise that, although many similar ones have been made, this one hasn't been copied before and that brings months of trial and error in order to start making accurate replicas."

"danger" - Google News

September 01, 2020 at 06:02AM

https://ift.tt/3lDTqOA

The traditional crafts in danger of dying out - BBC News

"danger" - Google News

https://ift.tt/3bVUlF0

https://ift.tt/3f9EULr

No comments:

Post a Comment