It was a brazen assault that put the extreme vulnerability of American military bases in Africa on full display. On January 5, 2020, members of the terrorist group al Shabaab attacked a longtime American outpost in Kenya, and when it was over three Americans were dead, two others were wounded, six aircraft had been wrecked, a fuel storage area had been destroyed, and the airfield—which had been considered a “safe area” for U.S. troops—was on fire and out of commission.

At the beginning of the attack, two U.S. contractors were taxiing their surveillance plane on the tarmac when a rocket-propelled grenade came streaking toward them. The assault was such a surprise that it took an hour for American troops to respond, and as many as eight hours to evacuate a private contractor that sustained injuries 1,500 miles away to a military hospital in Djibouti. Shortly after the assault, reports also emerged that many of the Kenyan soldiers assigned to protect the Manda Bay outpost fled and hid until the fighting was over. (The military’s Africa command, or AFRICOM, refused to respond to VICE News about these allegations.)

Months later, the United States military is still conducting an investigation into the attack. Personnel have been tight-lipped on the reasons why al Shabaab, an East African terrorist organization affiliated with al Qaeda, was able to deal the U.S. such a heavy blow, but one fact is clear: Measures to secure the base, also known as “force protection,” failed spectacularly.

Two sets of exclusive, formerly secret AFRICOM documents obtained by VICE News show that as many as 20 American outposts across Africa may be in similar danger of the type of debacle that occurred at Manda Bay. These files also suggest that Africa Command has taken steps to obscure information about the sites where local forces provided protection. Another batch of exclusive documents also reveals that the Manda Bay attack occurred not long after a sweeping security upgrade of the outpost, calling into question the efficacy of measures to protect that base and the safety of U.S. personnel stationed elsewhere on the continent.

“It’s highly likely that another attack like this will happen again somewhere in Africa,” retired Brigadier General Donald Bolduc, who served at U.S. Africa Command from 2013 to 2015 and then headed Special Operations Command Africa until 2017, told VICE News. “What’s going on in Africa, in terms of attacks on U.S. forces, is a classic example of poor policy, poor strategy, and a poor operational approach that endangers the safety and security of our service members.”

Africa Command still refuses to say if steps have been taken to remedy any existing security gaps and provided boilerplate responses to VICE News about security upgrades at Manda Bay, potential adjustments to force protection at other bases, and whether local forces were still providing critical security at most U.S. outposts in Africa.

“Force protection is one of the command's most important priorities,” spokesperson John Manley told VICE News. “We continuously assess force protection and security measures and make adjustments as necessary across the continent.”

While Manley declined to name locations, or even provide a simple count, of other bases where foreign forces provide security for U.S. troops, formerly secret 2019 AFRICOM planning documents reveal that local forces provided some or all of the “force protection function” at 20 U.S. bases across the continent. This means that Americans at the majority of U.S. military sites in Africa may be vulnerable to the security breakdowns that led to the deaths at Manda Bay.

Manley told VICE News that AFRICOM does not view force protection by local troops as a danger, but U.S. military history is replete with examples of outsourced security leading to the deaths of Americans. In 1965, an attack on an airfield at Pleiku, South Vietnam, whose perimeter was primarily defended by local forces, killed nine U.S. troops, wounded another 128, and destroyed a 122 aircraft. In October 2000, while refueling in a port primarily defended by Yemeni forces, the USS Cole was attacked by al Qaeda militants, resulting in the death of 17 American sailors. In 2012, Taliban forces penetrated Camp Bastion in Afghanistan, which was guarded by Tongan troops, killing two Marines and destroying six aircraft. An investigation led to the firing of two generals and a stark pronouncement by the Marine Corps Commandant, General James Amos: “Marines can never place complete reliance for their own safety in the hands of another force.”

An article in a 2014 Air Force anthology on air base defense also noted that that service branch “historically considered threats outside the air base perimeter the responsibility of either sister services or host-nation forces,” but that experiences in South Vietnam and during the Gulf War “demonstrated that these organizations may not have sufficient forces to perform exterior air-base defense missions effectively.” Another article in a 2019 follow-up anthology published by the Air Force’s Air University Press warned that a “host-nation force is unlikely to replicate the standard of U.S. forces” in terms of ensuring “appropriate levels” of base security.

Bases where force protection is provided by host-nation troops are also, the AFRICOM files show, predominantly located in countries where America has waged quasi-wars in recent years. U.S. forces have taken part in combat in at least 13 African nations over the last decade, according to former Special Operations Command Africa, or SOCAFRICA, commander Bolduc. Documents, obtained by VICE News through the Freedom of Information Act, show that 16 of the bases where the “host nation contributes to or provides the entirety of the force protection function” are in these same countries, including Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Kenya, Libya, Niger, Somalia, and Tunisia.

“The attack on Manda Bay wasn’t surprising,” said Bolduc, noting that there is a high risk of another attack like Manda Bay in the future, but that the dangers aren’t new and echo similar issues when he took command of SOCAFRICA, a subcommand of U.S. Special Operations Command under the operational control of AFRICOM, which oversees elite American commandos on the continent. “There was a lack of investment in force protection for our SOF [Special Operations forces] whether they were on host nation bases or in other areas,” he said. “I had 96 individual missions with 886 separate tasks in 28 different countries when I took command of SOCAFRICA, but had to carry that out with inadequate medical coverage, inadequate ISR [intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance] coverage, and inadequate personnel recovery assets.”

The losses at Manda Bay and U.S. actions after the attack suggest that the base was, indeed, under-resourced. In the wake of the al Shabaab assault, about 120 infantrymen from the 101st Airborne Division were rushed to the base and, according to President Donald Trump, unspecified “equipment” was also “deployed to Kenya to increase force protection measures.” (AFRICOM refused to provide VICE News with details about current troop levels or if steps were actually taken to increase security at the base.)

Additionally, the 2019 planning documents, which were drafted roughly one year and three months prior to the al Shabaab attack on Manda Bay, inexplicably do not list that airfield as one of the U.S. outposts where local forces provide security. The only facility in Kenya protected by local troops, according to the documents, is located in Mombasa, a coastal city about 200 miles from Manda Bay.

Bolduc told VICE News that as SOCAFRICA commander, he recognized Manda Bay as a critical sea and air base, visited often, and bolstered the outpost’s defenses with additional American troops “augmenting our host nation partners.” The dangers were also no secret, he explained. “We know that those local forces are—in the event of an attack—probably going to run. We know that there is a lot of corruption, so they may be paid off to run,” he said. “So, I made sure that we had adequate force structure there to protect it. I assume there were changes made.”

According to documents obtained by VICE News, upgrades to Manda Bay’s security were made prior to the attack. Exclusive 2018 Air Force documents reveal that there already had been “a sweeping upgrade of force protection at Manda Bay” between June 2017 and June 2018. The partially redacted documents, produced by the 449th Air Expeditionary Group, refer to the “construction of a new defensive perimeter” and the acquisition of an unspecified “capability” to provide security and protect $142 million in air assets then located at the base.

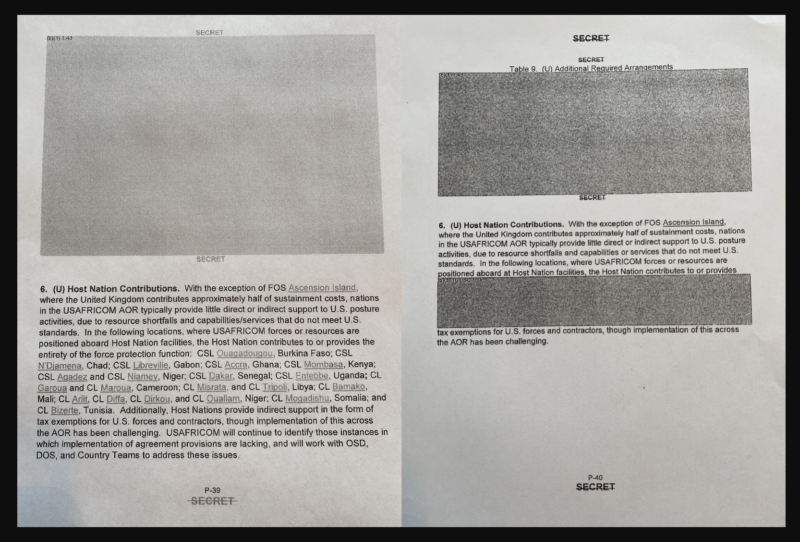

AFRICOM's 2019 planning document is on the left, and the 2020 planning document is on the right.

The files also note that during that same time span, Colonel Shawn Cochran, then the commander of the 449th Air Expeditionary Group, “championed a major shift in East Africa’s decade-old personnel recovery posture,” leading to a 75% decrease in the time between an alert about injured personnel and the time that help arrives. The files say that these changes were “ultimately mitigating risk to [the] United States and partner nation force nations.”

At least one other tangible action was taken by AFRICOM in regard to security provided by host nation forces at U.S. bases: In the command’s formerly secret 2020 planning documents, AFRICOM redacted all material relating to force protection by local troops, making it impossible to know which bases continued to rely on resident troops for the security of U.S. forces this year.

Compared side by side, the language in the 2020 documents is identical to the 2019 version, until the mention of host-nation contributions to force protection is redacted. Neither AFRICOM’s Freedom of Information Act office nor its communications office would offer an explanation for the decision to redact the 2020 files. “It would be inappropriate for me to speculate on the reasons why sections were redacted beyond established law,” AFRICOM’s John Manley told VICE News.

“It’s pretty obvious why they did it. We’re at all these places where troops are at risk, but they don’t want you to know about it. And if they had the right security, they would want to talk about it. That says a lot,” Bolduc told VICE News after reviewing the 2019 and 2020 AFRICOM documents. “It’s pretty clear that they don’t want Congress or the American people asking questions about it.”

Earlier this year, however, members of the House and Senate Armed Services Committees questioned AFRICOM commander Army General Stephen Townsend about the attack on Manda Bay. “I think it is self-obvious we were not as prepared there in Manda Bay as we needed to be,” Townsaid told the Senate Armed Services Committee, not mentioning the previous security upgrades that had been made to the Manda Bay base during 2017 and 2018. “Al-Shabaab managed to penetrate onto that airfield … they were able to get access to that airfield, kill three Americans and destroy six aircraft there. So we weren’t as prepared and we’re digging into that to find out why that’s the case.”

Throughout their questioning, the committee did not ask about any ongoing security risks to American bases posed by a reliance on local African forces. Senator Martha McSally, a Republican lawmaker from Arizona and 26-year veteran of the U.S. Air Force, questioned Townsend about the “surprisingly sparse security” at the Kenyan base and steps being taken “to make sure that others are not going to be in a similar risk.” But when the AFRICOM chief confined his answers to actions taken at Manda Bay, she asked no follow-ups about the broader issue of base security on the continent.

McSally, who once oversaw planning of counterterrorism operations in Africa, later issued a press release in which she stressed the “need to improve security of U.S. assets in Africa**,**” but, her staff said, she was unaware of the many other bases that may be as vulnerable as Manda Bay due to a reliance on local forces for force protection. “The Senator was never made aware of the aforementioned dangers you describe,” Amy Lawrence, her communications director, told VICE News. (McSally’s office ignored repeated inquiries from VICE News for further comment on the potential dangers to U.S. troops at bases across Africa.)

Congressmember Karen Bass, a Democrat from California and chair of the House Foreign Affairs Subcommittee on Africa, Global Health, Global Human Rights and International Organizations similarly failed to respond to questions about the potential vulnerabilities faced by U.S. forces across the continent. “The Congresswoman has previously supported calls for congressional investigations into these matters and all military activity across Africa in order to protect the lives of American citizens and their African counterparts,” said Janette Yarwood, the staff director of the subcommittee, in an emailed statement on behalf of Bass.

“We viewed and the Kenyans viewed Manda Bay as a safe area,” Townsend told the senators in January. ”And so I am looking with a clear eye at every location in Africa now.” To be certain, Benghazi and Manda Bay are far from the only attacks targeting Americans in Africa. The number of casualties from attacks on Americans by militants in Africa under the Trump administration is at least five times greater than the death toll at Benghazi, according to a tally drawn from press reports. These include the 2017 ambush in Niger by the Islamic State in the Greater Sahara that left six U.S. soldiers dead or wounded and an attack by al Shabaab in Somalia, just last month, that injured a U.S. service member.

More recently, reports emerged that AFRICOM is pressing for clearance to carry out drone strikes in portions of eastern Kenya as a result of the January attack. Last year, the Trump administration conducted 63 declared air attacks in Somalia, the most ever. This year, it has already conducted at least 47 strikes in neighboring Somalia, exceeding the number of U.S. air strikes in the country during the administrations of George W. Bush and Barack Obama combined. But expanding America’s drone war would likely entail expanding intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance capabilities, meaning even more contractors—the Americans who bore the brunt of the attack at Manda Bay—could be placed in harm’s way.

Elizabeth Shackelford, a former State Department Foreign Service officer who served in both Somalia and Kenya, questions the need for all the U.S. bases spread across the continent, noting that it is the U.S. military presence and activity in Africa that make Americans targets for extremist groups like al Shabaab. “It's shocking that practically no one even asked this question after the Manda Bay attack, but instead we're looking to double down and expand our authority to conduct drone attacks in Kenya now? It seems backwards to me,” she told VICE News.

Shackleford, now a fellow with the Quincy Institute for Responsible Statecraft in Washington, D.C., posed a different set of questions beyond those related strictly to U.S. base security, suggesting the need for a more sweeping reappraisal of the U.S. mission on the continent. “We've been building the U.S. military footprint in Africa for nearly a generation and with little real to show for it,” she said. “Our presence is risky and costly, and what does that, in fact, provide for the U.S. national interest? How does that risk and cost compare to what our real interests are? It isn't that I don't think we have national security interests in Somalia—it's just that I think no one has bothered to articulate them, measure them, and compare them to our strategy and the cost of our engagement.”

Nine months later, the military’s investigation into the attacks on Manda Bay grinds on with no clear end date, according to a Pentagon spokesman. “Work continues on the investigation,” Lieutenant Colonel Anton Semelroth told VICE News. “After it is completed, families and Congress will be briefed first, followed by the general public and news media.”

In September, a report released by the Pentagon’s Inspector General noted that “al-Shabaab moved freely and launched attacks in Somalia and Kenya,” that the group “conducted weekly cross-border raids and attacks on security camps in the Somalia-Kenya border region,” and that the violence had increased over the previous year with attacks in Somalia reaching “historically high levels” despite the Covid-19 pandemic.

Earlier this month, in apparent recognition of the risks facing U.S. forces there, SOCAFRICA commandos carried out a medical evacuation training exercise, involving the use of helicopters to provide rapid response to the injured, at Manda Bay. The same week, U.S. Army Major General Joel Tyler, AFRICOM’s director of operations, also visited the base, highlighting the threat posed by the terror group that attacked it, while talking up the dedication of America’s local allies. “Al-Shabaab remains a dangerous enemy,” said Tyler. “I saw first-hand the commitment of our Kenyan and Somali partners as we address a mutual threat in al-Shabaab. We will continue to sharpen our focus and counter this common threat.”

"danger" - Google News

October 27, 2020 at 03:00AM

https://ift.tt/3kvjBpO

US Troops Might be in Danger. Why Is the Military Trying to Hide It? - Type Investigations

"danger" - Google News

https://ift.tt/3bVUlF0

https://ift.tt/3f9EULr

No comments:

Post a Comment