Download our Free App

For Breaking News & Analysis Download the Free CBS News app

With her incisive, boundary-breaking works, the multidisciplinary artist has been exploring the nature of identity, and challenging assumptions about art-making, since the 1980s.

In January, the artist Lorna Simpson awed readers of Essence magazine with collages featuring photographs of that month’s cover star, Rihanna. The work was a continuation of Simpson’s ongoing “Earth & Sky” series, in which she replaces the hairdos of Black women in vintage advertisements with decoupaged images of precious metals and cosmic matter, challenging notions that our hair is anything less than sublime. The Rihanna collages spanned a dozen of the issue’s pages, in addition to the cover, and in each portrait the artist superimposed photographs she took of the singer over archival images sourced from The Associated Press, decades-old Ebony magazines and even 19th-century geological lithographs. In one work, Rihanna towers over an entire cityscape, larger than life (on set, Simpson directed her to walk and pose as if she were a giant); the contrasting scales of the background and foreground cast the singer in a different light than that in which she is typically portrayed — less musician or paparazzi subject, more mythical being.

Juxtaposition is a common motif in Simpson’s work, one that the artist often uses to present her subjects in ways that evade the white patriarchal gaze. It allows her, for example, to highlight at once in a single work the reductive ways in which pop culture and the media depict Black women, and their true beauty and multiplicity. She first conceived of “Earth & Sky” in 2016, when the election of Donald Trump sparked a national reckoning with America’s legacy of white supremacy; in the weeks and months that followed the release of the Rihanna images, a period that brought the Capitol insurrection and nationwide conflicts over mask mandates and vaccines, the country’s divisions seemed starker than ever. “As a human being,” Simpson told me recently, “the sense of people not giving a [expletive] about anything, I’ve always found that disturbing. Now, the masks are off on all levels; no more hiding under a guise.” During this period, the Brooklyn-born artist, who is currently splitting her time between New York and Los Angeles, has, she said, had to resist falling apart. The responsibility she feels to nurture the next generation (especially her 23-year-old daughter, Zora Simpson Casebere) has helped — and so has working.

Simpson, 61, has used her art to confound notions of gender, sexuality, race and history since the 1980s. A relentless experimenter, she crosses over into new media whenever she feels called to and has created a body of work — encompassing photography, painting, film and performance art — that has established its own more just and nuanced framework of reality, while also grappling with many of the defining external forces of its era, from racism to sexism to homophobia. In 1993, she became the first Black woman to show at the Venice Biennale, and she has continued to garner acclaim for disrupting assumptions about photographic portraiture, paving the way for her contemporaries and later generations of artists to be just as bold.

Growing up in Brooklyn and Queens, Simpson was immersed in the art world from a young age. She attended an arts high school, and her decision to pursue an arts degree at college was, she says, almost unconscious. Even before she started working as a photojournalist in the early 1980s, documenting street scenes in New York while an undergraduate at the School of Visual Arts, she considered herself an artist; her healthy ego was a shield against the racism and sexism — “old-timey bull,” as she calls it — she endured while a student there. This same confidence gave her the courage to create conceptual work on her own terms, as she did while enrolled in the master’s program at the University of California San Diego in the mid-’80s. When she presented her thesis project, which included “Gestures/Reenactments” (1985), a series of six gelatin prints showing different angles of a Black man’s torso accompanied by fragmented text captions, to the academic committee at her final review, she was met with silence, she recalls. “My work was above their heads,” she told me simply.

By the time Simpson moved back to New York in 1985, she was producing work that examined and pushed back against the stereotypes associated with Black women’s identities, including “Easy for Who to Say” (1989), in which each of five color Polaroids of a woman’s face is blocked out by an oval bearing one of the five vowels. Underneath “A” is the word “Amnesia,” under “E” is “Error,” followed by “Indifference,” “Omission” and “Uncivil.” “She,” a four-panel Polaroid work from 1992, similarly explores the gap between what is revealed and what is hidden, what is written and what is true, inviting the viewer to consider the creation of meaning; it shows the mouth, chin and body of a figure whose gender is uncertain but is seemingly proclaimed by the word “female,” which is mounted in cursive above the panels. Wearing an oversize suit, the subject oozes ambiguity and is smiling, almost defiantly, as if to say, “You can’t box me in.”

Both “Gestures/Reenactments” and “She” appeared alongside several of Simpson’s other early photo-text works in her pivotal 1992 solo exhibition, “For the Sake of the Viewer,” at the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, which came soon after her first major solo museum exhibition, “Lorna Simpson: Projects 23,” at the Museum of Modern Art in New York in 1990. Since then, Simpson has been consistently heralded as one of the most influential conceptual artists of her time. In 2007, the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York mounted a 20-year retrospective of her work, including photography from the late 1990s and early ’00s that abandoned the human figure completely — “Public Sex,” for example, a series of serigraphs made between 1995 and ’98, presents images of urban settings (a park, a fire escape, a public bathroom) and accompanying captions and grapples with the milieu of sexual titillation, voyeurism, emptiness, loss and death during the AIDS crisis — as well as early works of sculpture. The 2010s brought about Simpson’s celebrated collage works anchored by portraits of Black women cut from the pages Ebony and Jet magazines, including her ongoing “Earth & Sky” and “Riunite & Ice” (2014-present) series. And in 2019, she was awarded the J. Paul Getty Medal for her outstanding achievements in the arts.

For “Everrrything,” Simpson’s latest solo exhibition, which is currently on view at Hauser & Wirth Los Angeles, collage was again “a jumping-off point,” she says. The show’s nine works on paper coax new narratives from found images, inviting viewers to see contemporary American life through the artist’s eyes. Cutouts from archival issues of Black cultural magazines — an image of a woman from a 1970s Jet pinup calendar, another from an Ebony centerfold — feature in combination with renderings of galactic matter from 19th- and 20th-century celestial maps, as in the show’s multipart titular work, “Everrrything, 2021.” In one panel, the body of a partially nude woman, seated on the carpeted floor of a living room, is overlaid with a cutting from an 1810 woodblock print of a solar system. The image seems to point to the light-years of time and space contained within a Black woman’s existence, while also suggesting that these are erased within the one-dimensional medium of a pinup. In addition to collage works and paintings — which measure up to eight by 12 feet and which Simpson made by digitally enlarging vintage photos from Ebony, combining them with archival pictures of arctic landscapes, screen-printing those composites onto fiberglass and then painting over the resulting images with ink — the show includes several new sculptures. In the gallery’s courtyard, visitors are encouraged to interact with “Stacked Stones/Vibrating Cycles” (2021), which consists of large slabs of bluestone and wooden blocks painted blue — all of varying dimensions — arranged in 15 stacks of differing heights. The stones are intended to bring to mind the two cities Simpson calls home: Los Angeles, where the material is found in state parks, and Brooklyn, where it is used for “rail yards and platforms,” she says. On top of the piles sit obsidian singing bowls that evoke the ones Simpson plays in her home for relaxation; the work is both a meeting place, where visitors can commune around the stacks as they would at an intimate gathering with friends and loved ones, and a place of respite generously offered in a time, as the show’s title suggests, of seemingly unrelenting tumult.

Speaking over Zoom from Los Angeles earlier this month, Simpson answered T’s Artist’s Questionnaire. Seated in front of an abstract artwork (not hers) at Hauser & Wirth, she responded to each question thoroughly, always pausing for ten or so seconds first to gather her thoughts. We laughed, we shook our heads and, at the end of our conversation, we exchanged phone numbers.

What is your day like? What’s your work schedule?

The political and emotional toll of the pandemic has brought me to a place of pulling back from everything. It took me a while to get back into working every day. But working isn’t about just showing up in the studio. It isn’t so clear-cut in terms of its relationship to the WASPy, American idea of daily work and “putting in the hours.” It’s about thinking about things. I’ll wake up from a dream imagining things. So my intellectual and emotional relationship to what I’m doing doesn’t always happen in the studio.

What does your studio look like?

I have three different spaces. There’s my studio in the Brooklyn Navy Yard, which is for painting and collage. There’s enough space there to configure an entire exhibition. I can step back a good 60 feet and get a sense of the depth and iteration of paintings. Another space, in the David Adjaye-designed building in Fort Greene, Brooklyn, is used for archival work. The third is my home in Brooklyn. It has a courtyard and a garden, and that’s become very important for having conversations in person. The living room couch — from which we watch instances of white supremacy and insurrection on TV — is another space that is just as important when thinking about my work. So many things have happened across these spaces. Ideas flow through each of them.

When you start a new piece, where do you begin?

I always start with a sense that I need to just mess around. It’s important to begin those kinds of investigations without any other sense than pure experience and feeling. I’ve been making collages for a while, but recently I found all of these celestial maps. In them, there’s a Corona Borealis constellation. You can put a million objects in a collage but I limit myself to a certain amount of things. For a work in this show, for instance, that included an image from a 1970s Jet pinup calendar. On one side, it has a pinup, but beneath it there’s a Black history and achievements calendar. I kept the subject’s eyes to represent the masks we wear outside. But the original environment is supplanted with the galaxy. The galaxy has more to do with endlessness, instead of the narrowness that a pinup suggests. In the pandemic, it’s hard to think of making work. I’m blessed to have the relationship with the work that I do. With all the uncertainty, I’m still willing to try things and proceed from there — to trust that I will come out on the other side.

How do you know when you’re done?

I just do. It’s intuitive. I ask myself, Is it done? And if it is, I say, Oh, I think it’s done.

What’s the first work you ever sold? For how much?

I sold a work to a friend of my parents. I don’t remember for how much, as they only wanted a portion of the whole piece. It was one panel of text from “Gestures/Reenactments” (1985).

How many assistants do you have?

Only one, Jennifer Hsu.

What music do you play when you’re making art?

I have a playlist on Spotify. For the past two months, I’ve just played my “favorites,” anything that comes up that I like. It’s kind of amazing. Jason Moran — his “I’ll Play the Blues for You” — lots of blues. There’s “A Long Walk” by Jill Scott. “Kindred II” and “I’m Not in Love” by Kelsey Lu. And “Satisfied ’n Tickled Too” by Taj Mahal.

When did you first feel comfortable saying you’re a professional artist?

From a very young age, because my parents, who aren’t New Yorkers, decided to move there from the Midwest before I was born. They loved art and theater and would take me to everything. They really built a monster. How could you expect me to not be an artist? I was an only child. I went to an arts high school. Art was already unconscious for me. And by the time I got to college, at 18 or 19 years old, I was very aware of racism and sexism. It was 1979 or 1980, and even then, I was like, “Oh God.” My ego about that was already there, and then in my last year of college, at the School of Visual Arts, I was walking through Astor Place and there was this Häagen-Dazs shop. I remember reading somewhere that Häagen-Dazs is a made-up name for a company, it doesn’t mean anything. I was like, “People are just out here making stuff up — I can make stuff up.” The level of ego I took on … like, I have the privilege of making stuff up. I’ve always, in my career, pushed the bounds. When I started painting in earnest in 2015, I knew I was really messing with something. I have friends who’ve been doing that for 30 years.

All this is to say, I get to figure things out, I do it in a private way and then I get to judge it. Being a professional artist? That’s defined by my relationship to the work. It’s solely mine, my choosing, who I collaborate with, what kinds of conversation I’m in. I will never and have never let other people’s understanding of my work be a litmus test of my own value or professionalism.

Is there a meal you eat on repeat when you’re working?

Every few days while I’m in L.A. I go to Erewhon, a market here. It sells something called the wakame and kale salad. It’s really delicious and has a million things in it: kelp, kale, snap peas. I can’t make it myself because it’d take a hundred years.

How often do you talk to other artists?

Anytime I need to. A lot of them are my friends. When I wanted to paint, in 2015, I called up Glenn Ligon, who’d been excelling at it for decades. I talked to Okwui Enwezor, who asked me to send him a proposal before he considered putting me in that year’s Venice Biennale. And I’ve been in conversation recently with Robin Coste Lewis, who’s the poet laureate of Los Angeles. Part of our conversation has been around the millennia, not hundreds of years but millennia, in terms of measuring Black existence and bodies of color and Indigenous people. These conversations have been so amazing and freeing in this time of fighting over history and territory.

What’s your worst habit?

Procrastination.

What do you do when you’re procrastinating?

Send funny memes to my daughter from Instagram.

What are you reading?

Oh God, I don’t have it in front of me. It’s written by a Black physicist who talks about the language of science with respect to the theory of the universe. Terms like “black hole,” and other dichotomies of light and dark. She writes of her experience of being a grad student through to becoming a physicist. She talks about agency as a young Black woman in this field, about not being asked what she thinks in discussions, while watching her white counterparts be asked what they think. I’ve been reading it and thinking of our bodies as Black folk. Hundreds of years of white supremacy. Still, we don’t begin there, our bodies don’t begin there, our history doesn’t begin there. Not to say that that inflection point isn’t important, but we didn’t begin there. This has been freeing to think about because there has been so much denial about the reality of the relative present of the past hundreds of years. I texted my daughter for the title — it’s on my bedside: It’s Chanda Prescod-Weinstein’s “The Disordered Cosmos: A Journey Into Dark Matter, Spacetime & Dreams Deferred” (2021).

What’s your favorite artwork by someone else?

David Hammons’s “Phat Free” (1995/1999). The first time I saw it was in the office of the Whitney Museum curator Chrissie Iles, but I also recently came across it on Instagram and was brought right back to it. It’s so simple and mesmerizing and musical. He knows the sound of kicking a can along asphalt will have a certain resonance, and that the duration of time before kicking again will create another resonance, that catching up to it will create another resonance. That [expletive] piece.

This interview has been edited and condensed.

The fire danger in Summit County will decrease from high to moderate on Friday, Oct. 1, after several days of rain, low temperatures and even some snow at higher elevations.

Despite the decrease in danger, fire officials noted that caution is still required.

“While we are at moderate, our grasses and timber can still ignite,” Red, White and Blue Fire Protection District Deputy Chief Jay T. Nelson wrote in an email announcing the change. “Grasses are beginning to cure and seed for the season and can easily ignite even at moderate.”

For those planning to have an outdoor fire, Nelson said to ensure the fire is fully extinguished prior to leaving the fire ring.

As a Summit Daily News reader, you make our work possible.

Now more than ever, your financial support is critical to help us keep our communities informed about the evolving coronavirus pandemic and the impact it is having on our residents and businesses. Every contribution, no matter the size, will make a difference.

Your donation will be used exclusively to support quality, local journalism.

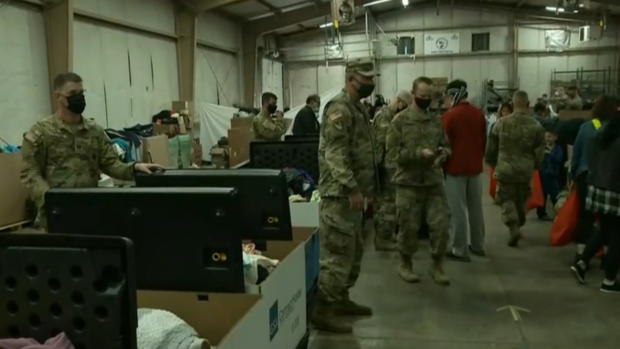

Surrounded by miles of farmland and cornfields, Fort McCoy is where life in America begins for nearly 13,000 Afghan refugees. On Thursday, a CBS News crew was allowed inside of the Wisconsin base, which houses the largest Afghan evacuee population in the U.S.

It's a chance for a life of freedom after desperately escaping the brutal rule of the Taliban.

"Before the current Taliban, I had a good life in Afghanistan," Farzana Mohammadi told CBS News.

The 24-year-old is ready for her new future. As a former member of the Afghan women's Paralympic wheelchair basketball team, she believes if she stayed in Afghanistan, life as she knew it would have been over.

"I can't go to basketball, outside of home, because Taliban not let women go outside," she said.

Many families have arrived at the base — which is one of eight U.S. bases helping to resettle more than 60,000 Afghan evacuees — with nothing but the clothes on their backs.

After reports of there not being enough food or clothing for the evacuees when they first arrived, base officials say there is now ample access to donated clothing, English classes and health care — including 29,000 COVID-19 vaccine shots donated over the past five days. They also have 1,500 soldiers providing security.

Earlier this month, two evacuees were charged with assault and sexual abuse.

"When the Taliban came and arrived in central part of our country, we felt in danger — unsafe," Sultana Amani said.

The Amani family fled Kabul with their five children. Now, 24-year-old Najibullah teaches a boxing class for men and women on the base. Their father, Mohammad Amani, hopes for a better future.

At this point, there's not a clear timeline on when families will be able to leave for their permanent homes — but they are expected to resettle across the U.S.

For Breaking News & Analysis Download the Free CBS News app

There’s a bit of verbal irony in the name The Many Saints of Newark, the title of the prequel to The Sopranos, one of the most groundbreaking, revered dramas in television history.

Turns out there are actually very few saints in the grim but still bustling pocket of mob-run Jersey circa the late 1960s and ’70s imagined for the screen by Sopranos mastermind David Chase, Sopranos writer Lawrence Konner, who co-wrote the screenplay, and Alan Taylor, director of the film and multiple episodes of the HBO series that inspired it. Practically everyone in this movie has a moral compass that’s gone kablooey or will in the near future. That’s especially true of Dickie Moltisanti (Alessandro Nivola), a character who never appeared in the HBO series but, according to this new chapter in the Sopranos saga, had a major influence on its central figure. (The title of the movie also works as double entendre: in Italian, many saints is “molti santi.”)

While this Sopranos prequel functions as a Tony Soprano origin story of sorts — even the movie poster asks, “Who made Tony Soprano?” — its protagonist is actually Dickie, a loyal member of the Soprano crew, semi-present father, and a less than faithful husband who is nevertheless admired by a young Tony, portrayed as a boy by William Ludwig and as a teen by Michael Gandolfini, son of the definitive Tony Soprano, the late, magnificent James Gandolfini. Even Tony’s mother Livia (an appropriately cantankerous Vera Farmiga sporting a prosthetically enhanced nose) looks at Dickie through glasses the color of the pinkest rose.

As the movie progresses, Dickie engages in increasingly heinous behavior — this Sopranos spin-off has lost none of the show’s willingness to display violence at its most brutal — while simultaneously reckoning with his anxiety and guilt. In other words, Dickie’s experience semi-mirrors the psychological journey that a grown-up Tony will embark on decades later, prompted by that famous family of panic-inducing ducks in his backyard swimming pool. With results that range from the predictable to the semi-profound, Dickie’s story also aims to enhance our understanding of the values that Tony emulated, absorbed and acted upon until The Sopranos’ final, controversial cut-to-black.

Theoretically a person could view The Many Saints of Newark, in theaters and on HBO Max Friday, without having seen The Sopranos, but I can’t imagine why anyone would. The basic plot is easy enough to follow, but the ability to notice connections between the two, along with the joy of recognizing the younger versions of familiar characters — the film is remarkably well cast — would be lost on the Bada Bing! deprived. And those are two of the central pleasures this movie provides.

When considered purely on terms that aren’t informed by its predecessor, Many Saints is a much thinner experience. Without six seasons of premium cable TV to add context, it plays out like a reasonably well-executed but not particularly inspired mob movie reminiscent of other mob movies you’ve probably seen before, and with an antihero in Dickie who lacks the depth and surprise that James Gandolfini’s Tony possessed in abundance.

The female characters lack the nuance and richness afforded to the men, which is unfortunate given how complicated the women in the series were. Here, they’re too often boxed into nagging wife or hot mistress roles, Livia being the closest to an exception. The movie also begins on an awkward note by panning through a graveyard, where the voices of the dead can be heard as the camera passes each of their tombstones, until it pauses on the one that belongs to Christopher Moltisanti (Michael Imperioli), son of Dickie and so-called “nephew” of Tony, as he begins to narrate the flashback that constitutes the rest of the film. That narration does not always seem vital, though it does pay off in pretty spectacular fashion in the final scene.

What is most thought-provoking about The Many Saints of Newark is what it says about mythologizing the past. In the opening moments of The Sopranos pilot, Tony tells his therapist Dr. Melfi (Lorraine Bracco) that he fears “the best is over” in terms of what’s possible in American life and that his father “had it better” in many ways. In this movie, Chase and Konner place us back in that supposedly better America. After all these years of being badgered about whether Tony lived or died following the jarring, vague conclusion of his series, Chase has responded by telling us what happened before rather than what happens next.

Immediately, the film shows us that Tony’s idealizations are a lie. Opening in 1967, the movie captures a Newark soon set ablaze by racial protests that are inspired by actual events of the time. We are introduced to Harold McBrayer (a charismatic Lamar Odom, Jr.), who played high school football with Dickie and now works as a numbers runner for him, but realizes he can’t rise much higher in an organization filled with blatantly racist white men. Early in the movie, Tony’s father, Johnny Boy Soprano (Jon Bernthal) is busted in a gambling raid and sent to prison for several years; when he gets out, he moves his family to the suburbs, already fleeing from the city that hasn’t fully declined but is heading in that direction. Even some of the narration plays like a scene from the most fucked-up episode ever of The Wonder Years. “That little fat kid is my Uncle Tony Soprano,” Christopher announces via voice-over as the camera settles on Ludwig’s Tony. “He choked me to death. But that was much later.”

In their own nostalgic way, fans of The Sopranos may look at The Many Saints of Newark for reminders of the series they used to love. The faint outlines are there. You can see them in the face of Michael Gandolfini, who does an admirable job of assuming the role his father made famous, and also looks so much like his dad that it makes your heart ache. You find it in the way that the film contrasts life’s darkness with normalcy and light, a trademark of the series. (A disturbing moment that plays out on a beach and is photographed in glowing light, with round light flares speckled across the frame, absolutely could have been in a Sopranos episode.) You see it in every acting choice that echoes the mannerisms of the mafiosos that we let into our living rooms regularly in the beginning of the 21st century.

But in its subtext, this movie tells us that nothing is as good as you might hope. That’s true of the era that Tony would later, wrongly, glorify. And it’s true of a movie that is fascinating to study and consider, but not nearly as good as the television series that made us wish for this movie to exist.

The family dog or cat in today’s world has many more opportunities to live a better life and take advantage of health care options that were previously unavailable or, in many cases, considered unimaginable for them. The human-animal bond has driven advances in medical research, specialized care, and innovation that have allowed pets to live longer, healthier, and pain-free lifestyles.

Our goal as an animal hospital accredited by the American Animal Hospital Association is to provide the best veterinary care possible for every animal that we have the privilege of serving. We also strive to give pets and pet parents the best experience possible by practicing fear-free methods that consider both the emotional and medical well-being of each pet. These are some of the reasons that clients with pet insurance are attracted to our animal hospital. When an insured pet comes in for a sick visit, the conversation changes from “How much will it cost?” to “How quickly can you figure out what is going on?”

During this day and age, pet parents have become used to “Amazon speed” instant gratification and immediate test results for their pets. One example of how technology has changed in our practice is with digital cytology. If you had asked me years ago if a lump or bump could be evaluated by a pathologist within minutes and then be removed by a surgeon at my practice the same day, I would have called you crazy.

Clients with pet insurance appreciate that we are getting them the most information in the shortest amount of time. They have developed a bond with their pet that overrides any potential issue with the cost of caring for their pet. They know that when they come to our practice and we take x-rays, they will have a radiology report within minutes so we can discuss the findings and best treatment options. These pet parents not only want but demand “concierge veterinary care.” They want to know immediately that their pet’s vital organs are working as they should. They are prepared for the costs because they see the value behind the information they receive and the beneficial outcome for their fur baby.

Another critically important aspect of having pet insurance is that it helps to ensure that no time is wasted during sick visits. Health insurance companies have made improvements to a preapproval process for sick visits to help expedite care for pets. Being able to preapprove a condition for insurance coverage results in a more efficient workflow and time saved, allowing the hospital team to manage cases more smoothly. When insured pet parents come in to our practice, we save the time that is usually dedicated to going over treatment plans as parents give us a green light to do whatever is necessary for their beloved pet.

In our profession we hear people say that their pet’s medical bills are as much or even higher than the cost of their own medical bills. People believe this is because they usually have their medical care bills paid through their health insurance. Imagine that you decided that if your children or family members ever suffered an injury, illness, or accident you would just pay out of pocket for their medical care. Some people might think you were unreasonable or irresponsible, unless you had a large amount of disposable income.

Most pet parents pay out of pocket for their pets’ medical expenses. This is easier to do if you bring in enough income to put money aside for your pets’ health care, but most Americans struggle to save money at all. More importantly, there is no way to anticipate what will happen in the future, so you cannot predict when or how your pets will get sick or how much it will cost.

Our pets’ lives come with uncertainties. No matter how careful or responsible we are, our puppies find and devour socks, our kittens climb and stumble off shelves, and we have a responsibility to provide them with the best treatment available. We love our pets, and pet insurance has become a necessary tool that enables us to care for them without excessive financial burden and added stress for pet parents.

At the very least, the average cost for an unexpected veterinary visit can range anywhere from $800 to $1500 or more. In many cases, a pet emergency visit leads to long-term care changes. When this happens, not only do you need to cover the cost of your emergency vet visit, you also have to factor in long-term costs to your budget. When a pet is seriously injured or develops a chronic illness, they will need regular treatment and medications to maintain their quality of life.

Considering that most Americans don’t have $1000 to spend in an emergency, it is troubling to think what could happen to a family if they were suddenly overwhelmed with expenses.

So the question you need to ask your clients is “Can you afford to have a pet without insurance?” If you are providing those clients with the excellent care that all pets deserve, the answer should be a resounding—no.

Boaz Man, DVM, is the owner and medical director of Boca Midtowne Animal Hospital, an American Animal Hospital Association—accredited facility in Boca Raton, Florida, and a Fear Free–certified professional.

[unable to retrieve full-text content]

Koeman's job in danger before Barcelona visits Atlético Daily Union

XI JINPING IS waging a campaign to purge China of capitalist excesses. China’s president sees surging debt as the poisonous fruit of financial speculation and billionaires as a mockery of Marxism. Businesses must heed state guidance. The party must permeate every area of national life. Whether Mr Xi can impose his new reality will shape China’s future, as well as the ideological battle between democracy and dictatorship.

His campaign is remarkable for its scope and ambition. It started to rumble in 2020, when officials blocked the initial public offering of Ant Group, an affiliate of Alibaba, a tech giant. It is thundering onward, having so far destroyed perhaps $2trn of wealth. Didi, a ride-hailing outfit, has been punished for listing its shares in America. Evergrande, an indebted property developer, is being driven towards default. Trading on cryptocurrency exchanges has been banned as, more or less, has for-profit tutoring. Gaming is bad for children, so it must be strictly rationed. China needs larger families, so abortion must become rarer. Male role models should be manly and celebrities patriotic. Underpinning it all is Xi Jinping Thought, which is being drummed into the craniums of six-year-olds.

This comes on top of an already brutal authoritarianism. As president, Mr Xi has purged his rivals and locked up over 1m Uyghurs. He polices debate and will not tolerate dissent. The latest campaign will show whether he is an ideologue bent on grabbing power for himself, even if growth slows and people suffer, or whether he is a strongman willing to temper dogma with pragmatism. His vision, in which party control ensures that business is aligned to the state and citizens dutifully serve the nation, will determine the fate of 1.4bn people.

Mr Xi is tackling real problems—indeed, many of them have parallels in the West. One is inequality. The slogan of the moment is “common prosperity”, reflecting how Communist China remains as unequal as some capitalist countries. The top 20% of China’s households take home over 45% of the country’s disposable income; the top 1% own over 30% of household wealth (see Free exchange). Another concern is the clout of tech giants accused of unfair competition, corrupting society and having unfettered access to personal data (only the state has that privilege). A third is strategic vulnerability, particularly the threat that adversaries will obstruct access to commodities and vital technologies.

Yet Mr Xi’s campaign poses a threat to China’s economy. Pain from unravelling the debt of firms like Evergrande could spread unpredictably. Property developers are sitting on $2.8trn of borrowing. Property development and the industries that cater to it underpin about 30% of China’s GDP. Households have parked their savings in real estate partly because other assets offer a poor return. Households’ spending on unfinished property accounts for half of developers’ funding. Local governments, especially outside the big cities, depend on land sales and property development to generate revenue.

The crackdowns are also making business harder and less rewarding. The party had been creating a regulatory and legal framework, but Mr Xi is imposing big top-down changes so fast that regulation has started to seem arbitrary. Consider, for example, “tertiary redistribution”, in which shamed tech companies hand over cash to the state in an attempt to redeem themselves.

Because conspicuous success is dangerous, private companies will be more cautious. State-owned firms and strategic industries—including “hard-tech” such as semiconductors—may benefit, but not the entrepreneurs who have been the true source of China’s dynamism. One measure of anxiety is that foreigners, who are not bottled in by capital controls, pay 31% less than mainland investors for identical Chinese stocks. The gap has grown sharply since early 2020.

All this threatens to puncture China’s economy. It was already facing a squeeze from declining returns to infrastructure investment and the effects of a shrinking workforce and growing numbers of aged dependents. After 40 years of breakneck expansion, most Chinese are completely unfamiliar with the hard choices that a sharp, sustained slowdown will impose.

In politics the danger is that Mr Xi’s campaign degenerates into a cult of personality. To bring about change, he has grabbed more power than any leader since Mao Zedong. As he prepares to break with protocol at the Communist Party’s 20th congress next year by claiming a third five-year presidential term, he is using the campaign to organise a huge turnover in personnel, as the basis for an ideological crackdown and as the reason why he should remain at the helm. Each of these contains dangers.

One is that the bureaucracy fails him. Mr Xi wants it to be responsive to market signals, but with promotions and purges in the air, China’s officials are jumpy. One cause of the power cuts in 20 or so provinces in recent weeks was the panic of bureaucrats who suddenly realised that they were likely to miss their carbon-reduction targets. Equally, however, officials fearful of being accused of corruption or ideological deviance by their rivals tend to sit on their hands. Failure is dangerous for a bureaucrat who takes the initiative; so is success.

Another danger stems from the ideological crackdown. “Moral review councils” and “moral clinics” are enforcing orthodox behaviour using public shaming. Although there is as yet no prospect of anything as awful as the Cultural Revolution, Chinese people are becoming less free to think and talk. As well as promoting his own doctrines, Mr Xi has played up Red nostalgia and cast Maoism as a vital stage in building a New China, broadening his support before the party congress.

Last come the politics of Mr Xi himself. In the long run, if he clings to power the succession could prove highly unstable. In the short run, if his attempt to impose a new reality does not go to plan, he will face a fateful choice to double down or step back. Up to this point, repression looks more likely than compromise.

Western governments are also struggling with tech firms, inequality and national security. In America Congress has risen to the occasion by contemplating a default on the national debt. Some may envy Mr Xi’s scope to get things done fast. But to imagine he has the right answers would be a big mistake. ■

This article appeared in the Leaders section of the print edition under the headline "China’s new reality"

After seizing on the lowest rates in history to extend debt maturities into the next century, Europe’s safest issuers have hit an impasse.

Ultra-long debt is on pace for its steepest declines in more than seven years, as rebounding growth and inflation prompt investors to dump the safest debt that’s most sensitive to interest-rate risk.

Chapel Hill, North Carolina — One reason many people hesitate to get vaccines – whether for COVID-19 or anything else – is a fear, or at least dislike of injections.

But researchers are working on an alternative way to administer vaccines they say would be pain-free, eliminate the need for injections and be self-administered: vaccine patches.

Teams at the University of North Carolina and Stanford University are developing the patches, reports CBS Raleigh, North Carolina affiliate WNCN-TV.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention says as many as a quarter of adults and most children have an aversion to needles. For some, it's so severe it keeps them from getting vaccines. But one day, needles, at least the ones people are used to, may not be necessary.

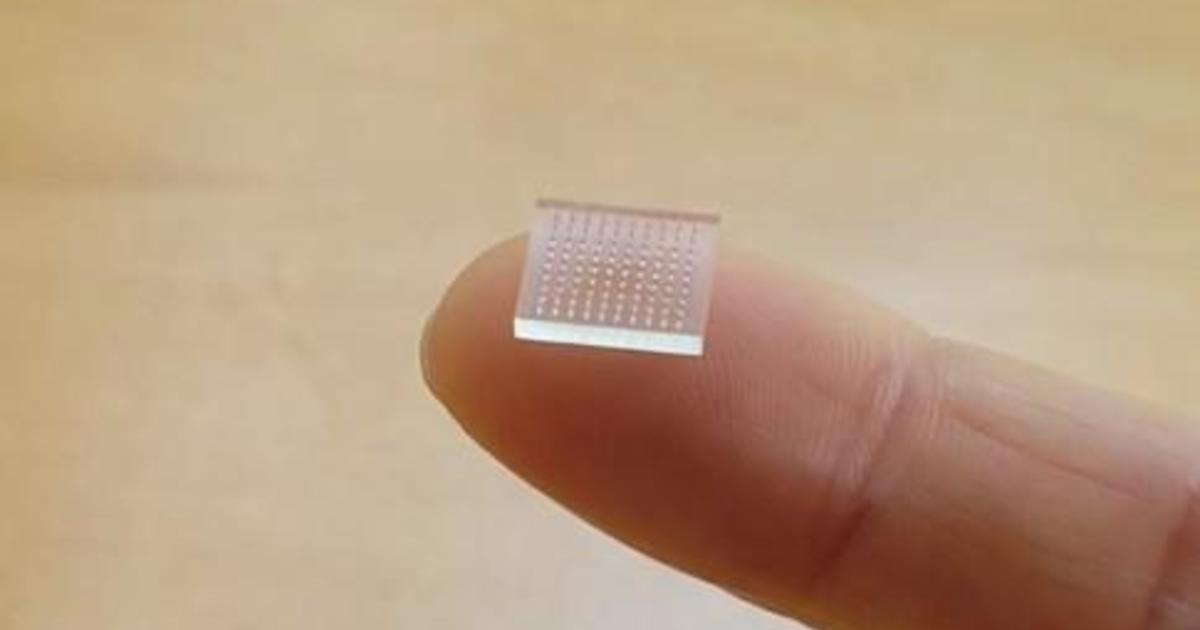

Dr. Joseph DeSimone worked at UNC for 30 years. He's at Stanford now, but he and his colleagues are still working with UNC researchers on a tiny patch that can deliver vaccines when applied to the skin.

"Our approach was to directly 3-D print the microneedles using a breakthrough in 3-D printing that we pioneered when I was in Chapel Hill," he told WNCN.

The microneedles on the patch are so small they can hardly be felt.

"It's pain-free and anxiety-free," DeSimone said, adding that the patch is also more effective than traditional shots. "We have 100 to 1,000 times more of the targeted immune cells in the dermis of our skin than we do in our muscle."

That means smaller amounts of vaccine would be required. It would also mean doses wouldn't need to be kept as cold as vaccines that are used in liquid form.

"When you think about global access, you are going to need things like that," DeSimone pointed out.

Right now, the patch is being tested on animals. DeSimone said the results are promising, and within five years, he expects people could be regularly using the patches.

"They can be self-administered. You wouldn't need a health care worker," he said. "They could be delivered by UPS or Amazon."

For Breaking News & Analysis Download the Free CBS News app

Sept. 27, 2021 --Sept. 29, 2021 -- Many patients with cancer, as well as doctors in fields other than oncology, are unware of just how much progress has been made in recent years in the treatment of cancer, particularly with immunotherapy.

This is the main finding from two studies presented at the recent European Society for Medical Oncology annual meeting.

The survey of patients found that most don’t understand how immunotherapy works, and the survey of doctors found that many working outside of the cancer field are using information on survival that is wildly out of date.

When a patient is first told they have cancer, counseling is usually done by a surgeon or general medical doctor and not an oncologist, said Conleth Murphy, MD, of Bon Secours Hospital Cork, Ireland, and co-author of the second study.

Non-cancer doctors often grossly underestimate patients’ chances of survival, Murphy’s study found. This suggests that doctors who practice outside of cancer care may be working with the same information they learned in medical school, he said.

“These patients must be spared the traumatic effects of being handed a death sentence that no longer reflects the current reality,” Murphy said.

After receiving a diagnosis of cancer, “patients often immediately have pressing questions about what it means for their future,” he noted. A common question is, “How long do I have left?”

Non-oncologists should refrain from answering patients’ questions with numbers, Murphy said.

Family doctors are likely to be influenced by the experience they have had with specific cancer patients in their practice, said Cyril Bonin, MD, a general practitioner in Usson-du-Poitou, France, who has 900 patients in his practice.

He sees about 10 patients with a new diagnosis of cancer each year.

In addition, about 50 of his patients are in active treatment for cancer or have finished treatment and are considered cancer survivors.

“It is not entirely realistic for us to expect practitioners who deal with hundreds of different diseases to keep up with every facet of a rapidly changing oncology landscape,” said Marco Donia, MD, an expert in immunotherapy from the University of Copenhagen, Denmark, said.

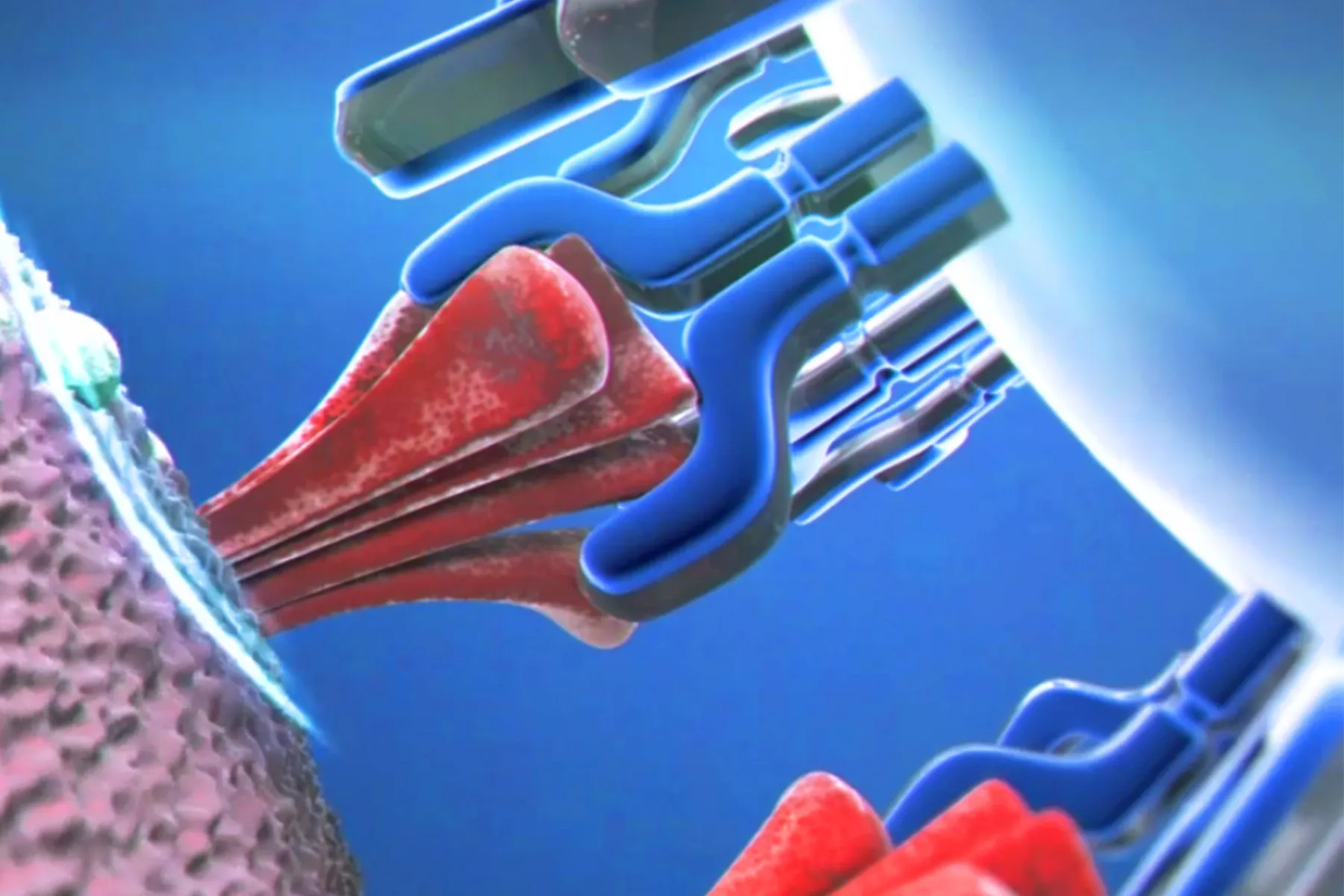

That landscape has changed dramatically in recent years, particularly since immunotherapy was added to the arsenal. Immunotherapy is a way to fine tune your immune system to fight cancer.

For example, in the past, patients with metastatic melanoma would have an average survival of about 1 year. But now, some patients who have responded to immunotherapy are still alive 10 years later.

Lt. Alex Cornell du Houx has dodged a sniper's aim, rocket fire and a roadside bomb. In some ways, the former U.S. combat Marine’s latest mission, an entirely volunteer one, has been his most challenging: helping at-risk Afghans escape the Taliban.

For the past six weeks, Cornell du Houx, now a Navy public affairs officer, has been part of a definitely-not-ragtag volunteer rescue force that swiftly mobilized amid the U.S. withdrawal.

After the Taliban captured Kabul, Afghanistan’s capital, on Aug. 15, U.S. and coalition aircraft combined to evacuate more than 123,000 civilians in the two weeks that followed, according to Gen. Kenneth McKenzie, commander of U.S. Central Command.

But many more Afghans – either through a lack of a visa, insufficient contacts or bad luck – were effectively marooned in newly hostile territory.

They were, or remain, in peril from reprisals from the new Taliban government because of links to U.S. and NATO forces, foreign aid groups and overseas media. They championed democracy, civil society, education, culture.

Motivated partly by concern at the way the U.S. withdrawal left so many behind – women’s rights activists, translators, journalists, politicians, Afghan National Army pilots, judges and female athletes – a volunteer coalition formed.

“It was the least we could do. We worked and, in many cases, served alongside these people for years,” said Cornell du Houx, 38, who combines work as a U.S. Navy public affairs officer with a civilian job running a nonprofit organization called Elected Officials to Protect America to address security issues related to climate change.

Navy Lt. Alex Cornell du Houx helped Afghans including Fatema Hosseini to flee the Taliban

Hannah Gaber, USA TODAY

The diverse group of volunteers – former and serving U.S. military personnel, Washington political veterans, intelligence community members, humanitarian aid workers, even an investment banker from Florida – pooled resources, contacts and knowledge to get Afghans evacuated on military and civilian flights to the U.S., Europe, the Middle East and Africa.

In fact, for about a week in mid-August, Cornell du Houx's newly founded group, EVAC (Evacuating Vocal Afghan Citizens), and other groups with names like Digital Dunkirk, Team America and Operation Eagle set up an ad hoc “command center” in the Peacock Lounge conference room of the Willard InterContinental Hotel in Washington.

The various units worked together, but also separately, on a dizzying array of logistical challenges ranging from chartering planes to securing landing rights in places such as Albania, Ukraine and the United Arab Emirates. They vetted local bus drivers to take people to Kabul’s international airport. They collected information on how to prioritize evacuees, knowing all the while these decisions could spell life or death and that many people were equally deserving of evacuation.

They also raised money, joined calls with U.S. administration officials and dealt with the panic and fear of Afghans who were trying to escape the Taliban. In some cases, volunteers provided step-by-step instructions to evacuees, advising them on which of the airport’s gates were open, what security precautions to take. They gave guidance about visas and paperwork.

Cornell du Houx had gone through a similar process in helping Afghan journalist Fatema Hosseini, who worked for USA TODAY, to escape with the aid of Ukraine’s special forces – and, a week later, her family. In both cases, he stayed up through the night to relay intelligence, coordinate with U.S. and Ukrainian commandoes on the ground in Kabul, and provide real-time tactical and emotional support to Hosseini and others as they navigated gunfire, tear gas and dangerous overcrowding around Kabul's airport.

"The whole thing was a rollercoaster ride, very tense," said Cornell du Houx. "I am trained to know what to do in combat situations but this was something else."

Iryna Andrukh, a colonel in Ukraine's military who alongside Cornell du Houx helped orchestrate Hosseini's rescue, then deployed to Kabul as part of a daring mission to save her family and dozens more, said of her country: "We always save those who are in trouble and ask for help." As part of that operation, Andrukh helped clear a path for buses to enter Kabul airport. This involved venturing into Taliban-held territory.

That success inspired EVAC, which Cornell du Houx estimates has now evacuated more than 500 people. It still has a database of about 5,000 names of people seeking a way out.

Scott Mann, a retired U.S. Army Special Forces officer who led a similar volunteer group named Task Force Pineapple, described his team’s efforts to help Afghans in a video message to supporters last month as an “underground railroad.”

The command center in Washington was partly funded by Zach Van Meter, a private-equity investor from Naples, Florida. Van Meter felt compelled to get involved after a friend and business associate of his, a former U.S. Army commando whom Van Meter in an interview would identify only as “Sean,” had reached out and said he knew of about 3,500 children, many of them orphans, who were stranded in Kabul.

“He asked me if I could help save lives. In that context I don’t think anybody could really say no to that. I didn’t really know what it entailed. I don’t think anybody really did,” said Van Meter, who leveraged his business contacts in the Middle East to assist the assembled volunteers.

Van Meter said his collaboration with the volunteers has altered his worldview.

“I've met so many people that don't live like I live, which was, you know, money, capitalism, sort of just push, push,” he said. “They live to save lives. They live to improve humanity. And so I now realize that part of my journey for the rest of my life is going to try to be more purposeful.”

I've met so many people that don't live like I live, which was, you know, money, capitalism, sort of just push, push. They live to save lives. They live to improve humanity.

A former U.S. Marine who had specialized in Special Forces reconnaissance was part of a 12-man American volunteer team that deployed to the Kabul airport Aug. 20. The former Marine, who declined to be publicly identified because he did not want to compromise continuing operations, said his group worked with U.S. military and high-ranking contacts in the United Arab Emirates to provide humanitarian assistance to an estimated 12,000 at-risk Afghans who eventually were evacuated to Abu Dhabi.

USA TODAY reviewed a series of communications involving the former Marine’s sources and his association with the evacuation effort, which appeared to support his account.

"We knew all too well the likelihood that America would abandon these people, and we were called into action to do the right thing ... to take care of those who had helped us," the former U.S. Marine said.

In all, about 3,000 volunteers from Alabama to Oregon helped Afghans escape in the days after Kabul’s fall to the Taliban, according to Heather Nauert, a former spokesperson for the U.S. State Department who has been working with volunteers and veterans organizations to ensure safe passage out of Afghanistan for families connected to the U.S. military.

“In many cases it was just suburban dads or moms like me making dinner in the kitchen for their kids, then jumping into action to see what we can do to help,” said Nauert, who described herself as someone who could “help shepherd cases” by filling out paperwork for people to get on flight manifests, calling senators’ offices and flagging particular cases to senior officials at the U.S. State Department and Department of Defense.

The Biden administration has come under criticism for a chaotic withdrawal that left many American allies and civilians vulnerable.

Rep. Ruben Gallego, an Arizona Democrat who chairs a congressional committee on intelligence and special operations, acknowledged that the “pullout could have been handled better.”

A former U.S. Marine who served in Iraq, Gallego spent several sleepless nights in mid-August contacting four-star generals and pressuring the State Department to get people to the airport in Kabul. He assisted volunteers with intelligence about road conditions and explored options to take evacuees to third countries, such as Qatar.

But Gallego said the evacuation represented “the best of America, whether it was the government or whether it was our our civilian side working together (with the government).”

The White House approved a plan for the Biden administration to formalize work with the network of volunteers, according to several volunteers familiar with the matter. This new public-private partnership followed a recommendation to the White House by the U.S.’s top military officer, Joint Chiefs Chairman Gen. Mark Milley.

Gallego is not directly involved with that effort. However, he said he expected it will be “a good way to get organized, help break through bureaucracy, and do a good effort to get people out of out of the country.”

Cornell du Houx is not waiting around for that to happen.

Shortly before this story published, he sent a WhatsApp message to USA TODAY:

“You can add to the count,” he wrote. “We just got 70 kids and 30 adults to safety.”

Contributing: Kevin Johnson

People confess their secrets to Wren Greenwood.

They don’t know her by that name. They know her as Dear Birdie, the nom de plume she uses for her wildly successful blog and podcast, where she advises the lost and broken-hearted.

“That’s what I do,” Wren tells us. “I help people solve their problems. My superpower is listening.”

But in Lisa Unger’s latest hold-your-breath psychological thriller, Last Girl Ghosted, Wren will need to find other superpowers — and deal with much greater danger than she bargained for when she swiped on a dating app.

This is the 19th novel in the string of bestsellers by Unger, who lives in Pinellas County. She just keeps getting better at writing irresistible thrillers; this one thrums with tension from its first pages and never lets up. As she’s done in several of her recent novels, such as last year’s Confessions on the 7:45, she takes the reader down a digital rabbit hole that has all too much impact on the real world.

Wren, like many people who are devoted to their jobs, has let her personal life slide. Though she’s young, single and living in New York City, she’s an introvert by nature and just about homebound. (The novel takes place just before the pandemic sets in — Unger threads in references to masks and news reports about a virus.)

Robin, one of her best friends since childhood, worries about the toll that being Dear Birdie takes on Wren emotionally: “It was a deluge of humanity in which I almost drowned.”

Jax, another of her closest friends, is Wren’s opposite: She’s gregarious, full of energy and determined to get Wren out into the world. Jax pushes until Wren consents to try an online dating site called Torch, although she’s dubious about the whole thing: “Modern dating. Let’s be honest. It sucks.”

But there he is. His photo is oddly unrevealing, his bio terse, but he quotes a line of poetry. Wren’s response: “Only a Rilke geek would know that line and what it meant.” She’s hooked.

When she meets Adam Harper at a bar, the connection is electric. For three months, their affair is all-consuming — great sex, great meals (both passions they share) and a deepening emotional bond.

At least that’s what Wren thinks, until Adam vanishes. One cryptic text and then nothing. His social media feeds vanish, his phone is dead.

At first she’s stunned and heartbroken. But then she starts to realize how little she really knows about him. She’s never met his friends or colleagues; his apartment, whose sleek style she’d admired, begins to seem more staged than minimalist. All she knows about his job is that he works in cybersecurity.

But Wren has secrets of her own. She narrates the book as if she’s speaking to Adam, but the repeated “you” has the effect of drawing the reader in so we feel we, too, have an intimate connection with Wren, whose voice is humorous and empathetic.

So when her secrets begin to slip out — for example, she’s never told Adam she’s Dear Birdie — our view of her subtly changes.

Heartbreak turns to alarm when Wren is contacted by Bailey Kirk, a private detective who has been hired by the parents of a girl named Mia Thorpe. Kirk shows Wren a photo of the man Mia had been dating. It’s Adam. And Mia has been missing for six months.

It’s tough to say much more about Last Girl Ghosted without giving away its many finely tuned twists and surprises. But I promise you it will be a dark and wild ride — and you might think long and hard next time you swipe.

Last Girl Ghosted

By Lisa Unger

Park Row Books, 400 pages, $27.99

Meet the author

Tombolo Books present Lisa Unger in conversation with Times book editor Colette Bancroft at a book launch for Last Girl Ghosted at 7 p.m. Tuesday at Coastal Creative, 2201 First Ave. S, St. Petersburg. Admission $10, which includes wine and snacks; tickets available at tombolobooks.com/events.

Oxford Exchange presents Unger at 6:30 p.m. Thursday at its Champagne bar. Admission $5, or $30.09 for admission plus a copy of Last Girl Ghosted; tickets at oxfordexchange.com/pages/calendar.

Times Festival of Reading

Lisa Unger will be a featured author at the virtual Tampa Bay Times Festival of Reading Nov. 8-14. festivalofreading.com

[unable to retrieve full-text content]

AAA: Oklahoma drivers do not fully grasp danger to roadside workers KFOR Oklahoma City/cloudfront-us-east-2.images.arcpublishing.com/reuters/SKXGOJAG6RMPZI63ECP24XSMHQ.jpg)

The company and law firm names shown above are generated automatically based on the text of the article. We are improving this feature as we continue to test and develop in beta. We welcome feedback, which you can provide using the feedback tab on the right of the page.

(Reuters) - Law firms that aren't covered by President Joe Biden's recent vaccine mandate because they have fewer than 100 employees have been left grappling with whether to independently require their lawyers to get the jab.

Many of the largest U.S. law firms have already responded to the rise of the COVID-19 Delta variant as well as the federal mandate by requiring those coming to the office to be vaccinated.

Though some midsize firms are taking more of a wait-and-see stance, many seem to be sharing their Big Law counterparts' approach, even if they employ under 100 people.

“Regardless of politics, it’s simply the right thing to do,” said Steven Molo, a founding partner at litigation firm MoloLamken.

MoloLamken, which has about 40 attorneys and fewer than 100 employees overall, was requiring vaccines even before Biden made the Sept. 9 announcement, Molo said.

Kane Kessler, which employs about 50 attorneys, decided in early August that all people entering offices on or after Oct. 4 be vaccinated. Before that the firm had "strongly encouraged" vaccines and already mandated mask-wearing in public office spaces.

Though the decision to mandate vaccines happened before Biden's announcement, Tullman said the federal order makes the firm's decision "more defensible."

At Kane Kessler, there is no way to opt out of the vaccine mandate unless an employee has a "bona fide medical reason" or a "genuinely held religious belief," according to Tullman.

Kent Zimmermann, a partner at law firm consulting company Zeughauser Group, said that midsize firms may be wary of drawing a line in the sand over vaccines, for fear they'll lose job candidates when the competition for associate talent is reaching record highs.

He said without the deep pockets of larger competitors, midsize firms are already at a disadvantage in the talent war, and so are hesitant to "alienate people who they need to attract and retain" through a mandate.

Most firms are already seeing a vaccination rate above 85% and are hoping the mandate question becomes a "non-issue," he said.

"They have a culture in which it's difficult to create mandates about anything where they could avoid it," said Zimmermann, who also noted that since partners collectively own firms, there is an added layer of complication.

John Giardino, managing partner for Los Angeles-based firm Michelman & Robinson's New York office, said the Biden administration's vaccine directive raised more questions than answers for the firm, which has more than 100 employees but not more than 100 in any of the firm's five offices.

"We're following the mandate - we know about it. We're waiting for the CDC to announce its response to it. And of course there's litigation going on so we imagine that the courts have something to say about it," said Giardino.

The firm has above 90% innoculation, according to Giardino, and 100% in New York. Employees can opt-out of vaccination and wear masks and undergo weekly testing. Giardino said the firm would comply with a mandate if necessary once guidance is clearer.

Texas midsize firm Sheehy, Ware, Pappas & Grubbs has an estimated vaccination rate of about 80%, according to Taylor Munn, the firm's business development coordinator.

While the 50-attorney firm promotes mask wearing in public office spaces and has "a plan in place" to encourage vaccines, there is currently no mandate and no plan for one, Munn said.

Read more:

Seyfarth Shaw just tightened its vaccine mandate. Will other firms follow?

Legal job ads hit new milestone amid talent crunch

Chinekwu Osakwe covers legal industry news with a focus on midsize law firms. Reach her at Chinekwu.osakwe@thomsonreuters.com.