California public health officials have begun distributing tens of thousands of coronavirus antibody tests from Abbott Laboratories to more than a dozen labs across the state as counties prepare to re-open and allow people to return to work, school and recreation. Other testing and health service companies are promoting antibody testing as a way to help people feel safer, get back to work and establish “a path toward normalcy for Americans.”

But in small print, a disclaimer required by the U.S Food and Drug Administration on some of these tests is stark: Negative results do not rule out SARS-CoV-2 and positive results may be false. State public health officials also have cautioned that it is still unknown whether accurate positive results mean protection from future infection.

The warnings show the challenge facing Gov. Gavin Newsom and other leaders as they attempt to lift restrictions and rekindle economic activity amid the COVID-19 pandemic: The technology needed for one of the most critical elements of their plan is still largely unproven.

“There is a lot of hype on antibodies, but we don’t even know for sure if antibodies drive long-term immunity in this disease,” said Dr. Ed Thornborrow, senior medical director for the UCSF clinical laboratories. “There is still a lot of work we need to do to get to, if you’re positive on an antibody test, you are immune and OK to go back to work.”

There are some encouraging signs, particularly with lab tests like Abbott’s, which has received FDA clearance through the agency’s Emergency Use Authorization process. Results from test runs performed by Abbott and other labs have returned false positive rates as low as 0.1% -- a key measure of accuracy for a test meant to flag whether people have been exposed to the virus.

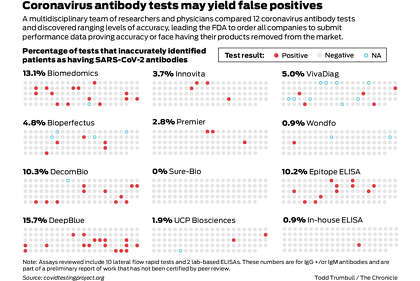

The FDA on Monday also cracked down on sales of unauthorized coronavirus antibody tests, requiring companies to submit performance data proving accuracy or face having their products removed from the market. The move followed reports by a team of Bay Area scientists and physicians and the National Institutes of Health revealing that a significant number of commercial tests were performing poorly since the FDA in March allowed antibody tests to be sold without prior authorization.

As of Friday, 12 tests had been given FDA emergency authorization, which involves a lower standard than the usual approval process. The agency said it is reviewing more than 200 additional tests.

In the meantime, antibody tests have become increasingly available to the public in just the last week.

Quest Diagnostics, which has 2,200 patient service centers across the country, is now selling antibody tests for about $130 a test through the company’s direct-to-consumer website. The requests are reviewed by a team of physicians. If approved, a person can then go to a service center to get their blood drawn with the results coming one to two days after. Similarly, on Wednesday, GoHealth Urgent Care -- one of the nation’s largest urgent care companies -- began allowing the public to schedule appointments online for antibody testing at its Dignity Health-GoHealth Urgent Care centers.

But there is still a ways to go to prove the viability of even the authorized antibody tests, and whether they can be used to make any determination about immunity. For now, scientists and public health officials have said the best use for antibody testing is in population studies that are trying to figure out how far the virus has spread, how it continues to spread and how protective antibodies really are by following individuals and collecting samples over time.

In the Bay Area, public health officials told The Chronicle they are taking a wait-and-see approach, with some going as far as recommending that individuals not take the tests -- unless they are part of a population study -- because of uncertainty over accuracy and what even accurate positive results might mean.

“The idea of testing resonates with people, but from an individual use perspective, the test doesn’t make a darn bit of difference right now,” said Dr. Bela Matyas, Solano County’s public health officer, adding that it’s premature and potentially risky for companies to be selling antibody tests as a measure of reassurance.

“The worry is that people will get a positive result, think they are immune and will fail to follow proper precautions and get exposed or transmit the virus to others,” he said.

Although antibodies are suggestive of immunity, scientists don’t yet know which antibodies might be protective, the level of antibodies a person might need to be immune, and how long any possible immunity could last.

Antibodies are one of the immune system’s key weapons against viruses, bacteria and other pathogens. Following an infection, the body forges these specific proteins to eliminate the current infection and to protect against future infection by the same pathogen.

Sometimes, like with measles, antibodies grant lifetime protection. Other times, like with the strains of coronavirus that cause the common cold, antibodies are less effective after only one to three years.

Doctors have used antibody tests for decades to determine whether people have immunity to diseases like the measles or chickenpox following vaccines or infection. For these tests, a patient’s blood is taken and then the plasma or serum is analyzed for antibodies. The current scramble to come up with an accurate and useful coronavirus antibody test, however, is unrivaled in modern history in terms of speed and scale, said Jason Cyster a UCSF immunologist.

“It appears the number of tests that have already been developed for this exceeds anything that has been done for any existing infection,” Cyster said. “But quality control takes time.”

The key challenge in developing an antibody test for SARS-CoV-2 is figuring out whether the antibodies flagged in a given test actually indicate immunity to a future infection and, if so, to what extent and for how long.

Even if antibodies do grant some amount of protection, it is unclear whether a person might still be able to get infected and become contagious, raising the possibility of people potentially being sent back into society who can carry and spread the virus, said Eva Harris, a UC Berkeley infectious disease expert.

“I’m petrified of that prospect,” Harris said. “Everyone wants these answers yesterday, but the science, itself, can only move so fast.”

Harris is part of the effort to get some of those answers. On Tuesday, Harris and UC Berkeley epidemiologist Lisa Barcellos sent flyers to residents in 11 East Bay cities, launching a months-long study that will follow and repeatedly test thousands of people in the East Bay to get a better idea of how asymptomatic infection and disease prevalence changes as social distancing measures are lifted, and whether people who have antibodies can be re-infected.

But the incredibly low incidence of infection in the Bay Area -- some scientists believe it may be as low as 1% - means that the antibody tests for these studies have to be very accurate to pick up the relatively few people who were infected and then developed antibodies.

Local scientists and researchers are now turning to more than one test, sometimes in combination, to get more accurate results.

“This is a big issue,” Harris said. “The tests out there have only been validated for sick people, yet most of the people these prevalence surveys will be measuring weren’t sick, or had mild disease.”

To detect as many true positives as possible, Harris’ team will be running all their specimens through two different antibody tests. Similarly, a large-scale study that is being done by Stanford and UCSF will also run all of its positive results through two different antibody tests that use different pieces of the virus, making a specimen that turns up positive on both much less likely to be an error.

“We want to find the positives, which means we have to look harder for them and test more,” said Dr. Yvonne Maldonado, a co-lead on the Stanford study and an epidemiologist and infectious disease expert.

In the meantime, the warnings and caveats have not deterred people from seeking out antibody tests and health care centers and testing sites from selling them.

Dr. Alexa Bisinger, the California medical director of Dignity Health-GoHealth Urgent Care said that within hours of offering antibody tests to the public on Wednesday, hundreds of appointments had been booked in the Bay Area.

During the health crisis, the company said there will be no out-of-pocket costs for in-network patients with commercial insurance. Dignity Health-GoHealth Urgent Care performs the blood draw for the antibody test and then sends the blood to Quest for testing. Quest then bill’s the patient for its lab services.

GoHealth Urgent Care is also providing the tests to companies that might want to incorporate them in their back-to-work programs.

Bisinger said that health care providers will explain test limitations to patients and that aggregated data will be shared with public health agencies and researchers to give them a better idea of infection prevalence.

“On the individual level, demand seems like it has been pent up and really exploding,” Bisinger said. “I think people want to be reassured and they want hope.”

That is in part what has led many people to seek out antibody testing. But often the results end up raising more questions than they answer. Some who fell seriously ill earlier this year with COVID-like symptoms -- persistent fevers and shortness of breath -- have still tested negative, even as others they live with have tested positive.

Dr. Matt Willis, Marin County’s public health officer, said he has received many emails from the public and friends who want to get tested for antibodies because they suspect they might have had the coronavirus. But Willis said the low incidence of infection in the area means they probably did not.

“I tell them you will likely be negative,” Willis said. “And it either means you were not infected, or you were and it’s wrong.”

Willis knows about inconsistent antibody results from personal experience. After he and a family member were both sick in March and tested positive for the coronavirus he also wanted to see if they had developed antibodies.

Yet only Willis initially came back as having antibodies in the tests they took at a local clinic. After another week, however, his family member took another test and came back positive, too.

“Everyone’s immune system is different and it may lead to different results,” Willis said. “So what that said to me is there is a lot we still don’t know.”

Cynthia Dizikes is a San Francisco Chronicle staff writer. Email: cdizikes@sfchronicle.com Twitter: @cdizikes

"many" - Google News

May 09, 2020 at 10:00PM

https://ift.tt/2LfMKFK

Coronavirus antibody testing: Much promise, many questions - San Francisco Chronicle

"many" - Google News

https://ift.tt/2OYUfnl

https://ift.tt/3f9EULr

No comments:

Post a Comment