Our news is free on LAist. To make sure you get our coverage: Sign up for our daily coronavirus newsletter. To support our nonprofit public service journalism: Donate now.

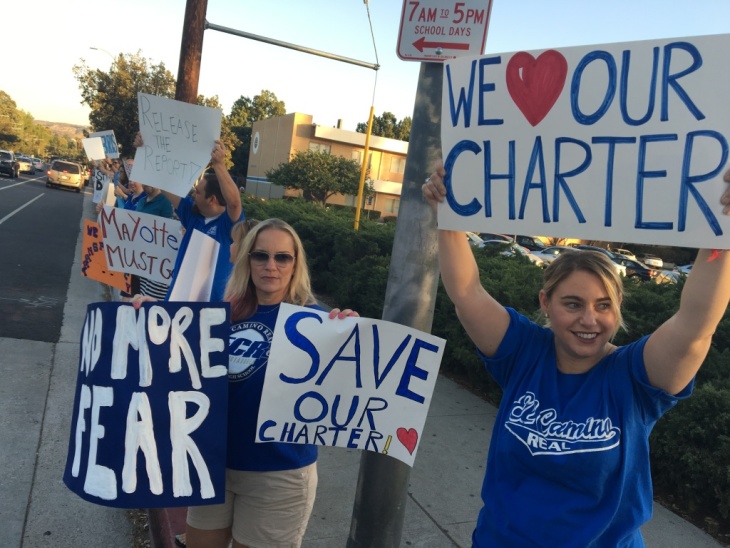

Two months ago, after a teachers union protest, KPCC/LAist identified a handful of Los Angeles charter schools that had accepted money from a now-$659 billion federal loan program aimed at helping small businesses stay afloat during the coronavirus pandemic.

Back then, we didn't know how common it was for charter schools — publicly-funded, tuition-free schools — in the L.A. Unified School District to receive loans from the Paycheck Protection Program, or PPP.

After our own analysis of federal data and charter schools' board documents, we now have a much better idea how common it is. The answer: very common.

- So far, lenders have granted PPP loans to 50 different organizations that run charter schools in the L.A. Unified School District.

- These 50 loan recipients collectively run more than half of the 224 charter schools in LAUSD.

- In LAUSD, charter schools' PPP loans total at least $73.6 million, but because the Small Business Administration doesn't publish precise loan amounts, the total could be as high as $136.7 million.

CHARTER SCHOOLS & THE 'DOUBLE-DIPPING' DEBATE

Last spring, Congress created the Paycheck Protection Program to help employers struggling to make payroll and rent amid the uncertain economic conditions brought on by the pandemic.

Since PPP's inception, watchdogs have raised questions about whether these emergency loans have been reaching their intended targets. See: restaurant chain Shake Shack returning its PPP loan amid public outcry.

Compared to the Shake Shack controversy, there's far less debate about whether charter schools can qualify — at least legally speaking. Charters are run by nonprofit organizations, and nonprofits with fewer than 500 employees are eligible for PPP loans.

"It's not like they're sneaking into the program," said Ricardo Soto, the chief advocacy officer for the California Charter Schools Association.

But teachers unions and other critics contend PPP money was not truly intended for charter schools.

Unlike other small businesses, charters' primary revenue stream — from the state and federal governments — has not stopped flowing during the pandemic. By borrowing these sums, critics say charter schools are diverting money meant for cash-strapped employers struggling to pay rent or make payroll.

"It's not right for charters to act like a business on Monday and a public school on Tuesday," said Clare Crawford, a senior policy advisor with In The Public Interest, a nonprofit policy and research center that's skeptical of charter schools.

"Having it both ways," Crawford said in a statement, "leads to double dipping and unethical raids on the public till."

Defenders point out that, like their district-run peers, charter schools are also handing out meals to families, buying new laptops for distance learning and shouldering other extraordinary costs of pandemic response — but unlike big school systems, Soto said charter schools have limited options to pay for these expenses.

For example, LAUSD used voter-approved bond dollars to purchase laptops for all of its students; charter schools can't bring bond issues to the ballot.

"This was a lifeline for [charters] to be able to continue to operate," said Soto, "and serve their students, serve meals and provide security to their employees at a time when there was a lot of uncertainty."

But a PPP loan could potentially do far more than shore up cash flow. If borrowers use PPP money on essential expenses like payroll or rent, federal officials intend to forgive the loans. Rather than bridge loans to weather a financial crisis, Crawford says some charters are using PPP loans as low-risk lines of credit.

"What we're seeing in many [charter school] board documents," said Crawford, "is people saying, "Hey, worst case scenario, we get a 1% interest loan'."

Crawford also contends the state and federal governments did set aside funds to help charters manage these costs. In total, 220 LAUSD charter schools received $33.3 million in dedicated aid from the CARES Act. (District-run schools participating in the federal government's Title I program got this money, too.)

MANY CA SCHOOLS — CHARTER OR NOT — WILL HAVE TO BORROW

California's publicly-funded schools are also bracing for a hit to their cash flow. The state balanced its budget this year by planning to delay payments to public schools — which means many public schools will be forced to borrow money one way or another.

While big districts can borrow at more-affordable rates, Soto said many charter schools might otherwise have to borrow at rates in the high single-digits; charters can't beat the 1% interest rate of a PPP loan.

The deferrals began last month — and some school leaders say the impact was immediate.

Greg Wood, the chief business officer at Palisades Charter High School, says a $4.6 million PPP loan was instrumental in allowing the school to make payroll in June.

"That's the ultimate definition of 'paycheck protection,'" said Wood, adding that Pali High faces more than $6.5 million in deferred state payments in the coming year.

The protection only extends so far. Three weeks after accepting the PPP loan, Pali's governing board voted to notify five non-teaching employees that their jobs might be eliminated in 60 days. Another 18 staff — campus safety aides, office workers and a cafeteria clerk — might see their hours reduced. Wood said none of the cuts have actually been carried out yet.

WHAT WE FOUND IN THE PPP DATA

A few takeaways from our dig through Paycheck Protection Program data:

- In LAUSD, most PPP funds went to small charter school operators. Of the 50 charter organizations that received PPP money, 36 operate one or two schools in LAUSD. The average number of jobs reportedly "retained" by accepting these loans was 158.

- In LAUSD, most PPP loans are small enough that they'll have less federal oversight. While PPP borrowers have to certify that their loan meets a legitimate need, the U.S. Small Business Administration has decided to certify that all loans under $2 million were taken out in good faith. Only seven loans to LAUSD charters were for $2 million or more.

- In LAUSD, most PPP loans weren't approved until after Congress re-filled the pot. After banks began taking applications on April 3, the first round of PPP funding quickly ran out — and many small businesses reported difficulty accessing the money. But in LAUSD, most charters — 36 out of 50 — had their applications approved after April 24, when President Trump approved an extra $321 billion for more PPP loans.

- Two administrative offices of large LAUSD charter networks received PPP funds. Some larger charter networks have separate entities that handle administrative functions and "national" operations. We included two organizations that run LAUSD charters in our dataset: Green Dot, which operates 16 charter schools in LAUSD, received a loan of $1-2 million for its national office. (Federal data only lists loan amounts as a range.) PUC National, which is linked to three separate organizations operating 11 LAUSD charters, received a loan of less than $350,000.

- The largest LAUSD charter networks don't appear to have applied. Alliance for College-Ready Public Schools, which operates 25 charters in LAUSD, appears to have not applied. KIPP L.A., which operates 15 charters in the district, also doesn't appear in the Small Business Administration's database.

THE LARGEST PPP LOAN WE FOUND IN LAUSD

Granada Hills Charter High School, the sought-after charter in the north San Fernando Valley, received a PPP loan of more than $8.3 million — the largest loan amount we were able to directly confirm in board documents.

In our database, Granada's loan is not only unusual for its size. With its PPP money, Granada officials reported they would retain 443 jobs, the most of any charter in our dataset. Unlike most LAUSD charters, Granada received its loan on April 11 — a time when many other prospective PPP borrowers were struggling to win approval.

Granada does have money in the bank. In June, school officials reported they had about $15 million in cash reserves — equivalent to roughly 20% of the school's expenditures.

When told of these figures, Crawford questioned why Granada would need a PPP loan: "They don't have the need for the funds," she said in an interview.

Granada's executive director, Brian Bauer, contended the situation is more complicated.

Bauer said the school's reserve alone is not enough to weather the state's payment deferrals: "Conservatively," Granada expects a total of $13 million in funding to arrive between two and six months late. The school also faces higher payments on a facilities bond and will take a hit from a change in state law that freezes funding for growing schools. The PPP loan will help bridge the gap, Bauer said.

"The only thing certain right now is the ongoing uncertainty," said Bauer.

STATEWIDE PICTURE

The findings in our newsroom's analysis of charter data mirror the findings of In The Public Interest's much broader look at charter schools across California receiving PPP loans.

Along with volunteers from Parents United for Public Schools, Crawford and In The Public Interest found California charter schools received at least $240.7 million — and potentially more than half-a-billion dollars — in PPP loans.

Not all charter schools in L.A. County are authorized by LAUSD. In the county as a whole, the organizations identified 75 loans, worth at least $89 million.

In Orange County, the organizations found 15 PPP loans to charter schools worth at least $17.3 million.

The organizations identified several loans they likened to Shake Shack's returned PPP funding: more than $51 million in loans to 12 different business entities all belonging to California's Learn4Life chain of charter schools, which reportedly employs more than 1,900 people across those entities.

Crawford said local charter school regulators — often the districts and county boards that authorize them — should be asking questions about how charters have spent this money.

And as state and local governments consider more aid for public schools during the coronavirus crisis, Crawford urged policymakers to prioritize schools that did not receive PPP money — including larger charter schools — for additional funding.

"It's not saying, 'Let's never give these schools another dime,'" she said. "There are a lot of schools that didn't access this money, so let's start based on need and reinforce equity."

"many" - Google News

July 31, 2020 at 02:51AM

https://ift.tt/3124Cv3

Why So Many LAUSD Charter Schools Ended Up With Coronavirus Relief Loans For Small Businesses - LAist

"many" - Google News

https://ift.tt/2OYUfnl

https://ift.tt/3f9EULr

No comments:

Post a Comment