At 4 p.m., two patients in respiratory distress arrived at Sharp Grossmont Hospital in La Mesa, one by ambulance and one brought in by loved ones through the main entrance. Then word arrived that yet another patient, this one suffering a stroke, would be delivered by ambulance in 10 minutes.

For most of its history serving a vast swath of East County, three cases in 10 minutes would barely be worth mentioning for the region’s busiest emergency department. But with more than 70 patients already occupying beds on the unit, three more equaled a full house, and it was time to once again begin the process of shifting patients around.

“This is the game we play now,” said ER manager Paul Larimore. “If that stroke code that’s going to be here in a few minutes ends up requiring an aerosolizing procedure, like if they’re not maintaining their airway, we should be in a negative pressure room.”

With a larger percentage of patients testing positive for the novel coronavirus, it is best to initially assume everyone is infected, especially if the problem they arrive with is likely to spray respiratory particles into the air.

At Sharp Grossmont Hospital on Thursday, nurses in the COVID unit respond to an alarm sounding in a patient’s room.

(Nelvin C. Cepeda / The San Diego Union-Tribune)

Putting newly-arrived patients in rooms with their own separate ventilation systems creates a margin of safety that helps keep the virus from spreading among vital health care workers and uninfected patients.

Though every such room was occupied when Grossmont learned of its inbound stroke patient Thursday afternoon, luck had it that the results of another patient’s coronavirus test returned negative, allowing him to be moved to a regular bed surrounded by curtains, freeing a negative pressure room just in time.

And so it goes with a full emergency department. Full occupancy sometimes means the safest option for patient and staff will not be immediately available when a surge of sick patients arrives all at once.

Increasingly, the current surge of coronavirus cases, coming alongside significant demand from those without the disease, is making it less and less likely there will be the right kind of empty bed available in the moment when it’s most urgently needed.

At Sharp Grossmont Hospital on Thursday, patient level and bed use and availability is tracked.

(Nelvin C. Cepeda / The San Diego Union-Tribune)

Sometimes, that has meant some patients being temporarily held or treated in hallways awaiting transfers to other facilities. Other times it has meant patients with life-threatening conditions remaining in the ambulances that brought them for hours on end until the bottleneck loosens.

The situation reached an ominous inflection point last week with the county emergency medical service announcing a new rule that allows overburdened emergency departments to relieve the pressure of too many simultaneous patients by temporarily diverting all ambulances save those with medical conditions so dire that death is imminent.

Grossmont, officials said Thursday, was forced to take just such a step last weekend, halting new ambulance arrivals for an hour in order to give its staff time to catch up. Dr. Kristi Koenig, medical director of the county’s emergency medical system, said in an email Saturday that her department now has two duty officers monitoring the situation round the clock, an unprecedented level of vigilance as the situation has “become periodically critical.”

Nurses put on new gloves and gowns and wear a PAPR before entering a room with a patient who has COVID-19.

(Nelvin C. Cepeda / The San Diego Union-Tribune)

Ambulance diversions, she said, continue though “only for a few hours at at time,” giving hospitals “time to decompress and adjust to free up more space.”

The county has so far declined to state which hospitals are going on total ambulance bypass and when.

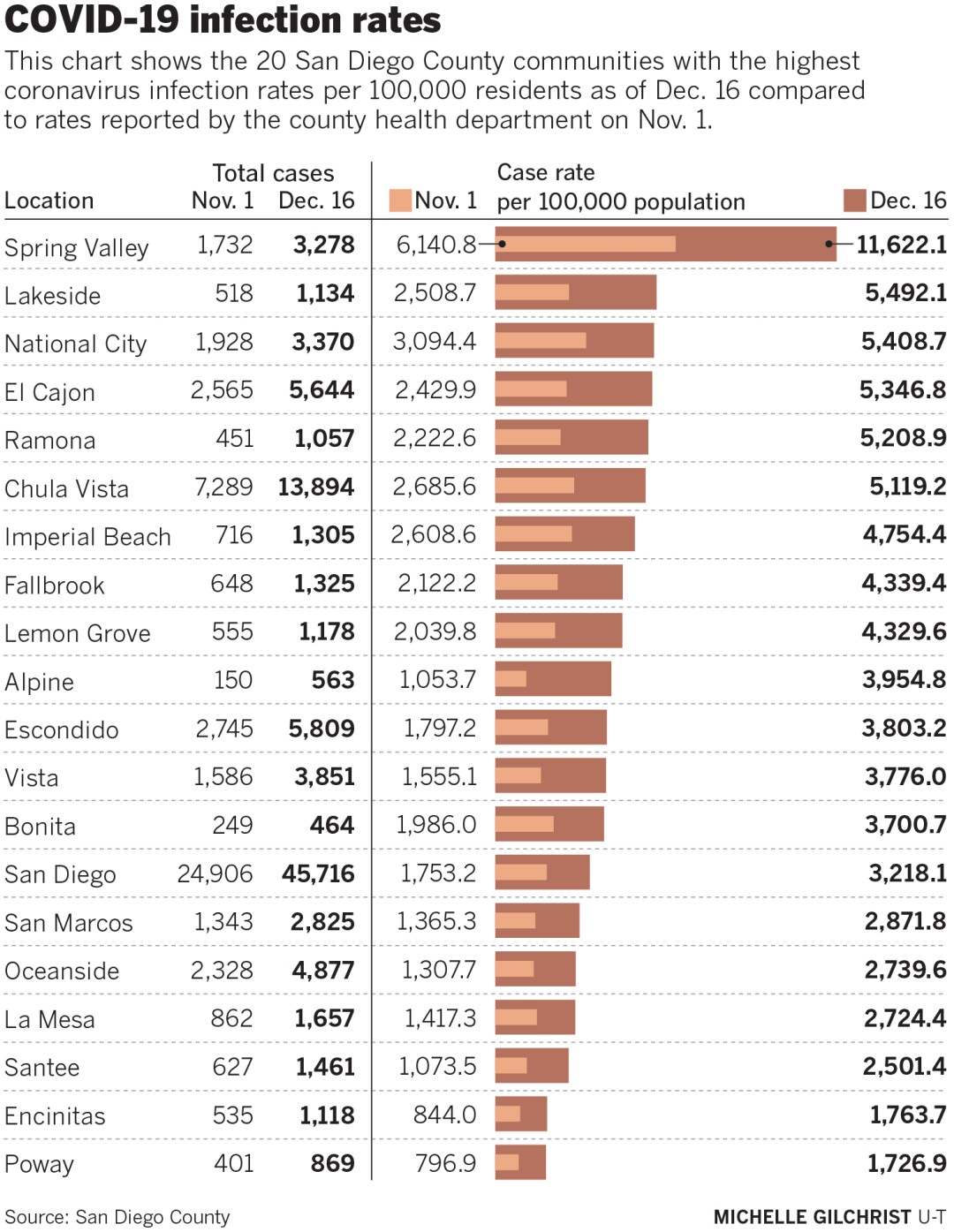

The furthest east in San Diego County, Grossmont is closest to the places, such as El Cajon and Lakeside, that have recently seen the largest increases in coronavirus infection rates, according to the city-by-city breakdowns that the county health department updates daily.

There were 20 patients, a mixture with and without COVID-19, waiting for hospital beds to open up at Grossmont Thursday afternoon.

One month ago, there would be five or six waiting for beds to open, said Marguerite Paradis, the hospital’s director of emergency services and critical care. Today, the number sometimes climbs as high as 30. Though the hospital has already converted specialty units and their staffs to serve COVID-19 patients, there is only so much expansion that is possible with every hospital in the nation simultaneously demanding all available medical staff.

At the emergency Room of Sharp Grossmont Hospital on Thursday, nurses stand to assist doctors and nurses inside the negative pressure room.

(Nelvin C. Cepeda / The San Diego Union-Tribune)

Generally, Grossmont’s staff has been able to keep up with demand. But sudden surges of ambulance deliveries in a short period of time can create conditions where there is simply nowhere to find more space.

Keeping patients on ambulance gurneys for hours can be the only option, but it is no solution. Paramedics cannot return to the field to care for the next round of patients, and people with severe medical problems are delayed in finding solutions.

“Those patients on gurneys don’t really get, other than a basic evaluation and vital signs, anything else, so it gets to be dangerous if we don’t have them in a bed,” Paradis said.

Though the situation in the Grossmont ER has not yet gotten to the point where the system falls apart, Larimore said things felt particularly dire during a massive surge of newly-arrived emergency patients last Tuesday.

Always advising his fellow workers to “stay water” and maintain ultimate flexibility in a situation where any kind of problem may come through the door at any moment, Larimore said that Tuesday shift definitely tested his ability to stay afloat.

“It was like we were under water and when you hit that two-minute mark where you’re like, ‘oh, I’m gonna ...’ and then we got a little bit of air,” he said. “We got a few beds upstairs, and we were able to get them up and get the next criticals in.”

A month or more ago, Grossmont routinely had somewhere around 30 COVID-19 patients at any one time. Last week, the number was north of 130 with no end in sight as a fresh record for new cases was announced Friday. Everyone who works in a hospital knows that a certain percentage of those newly positive will inevitably need hospital-level help two to three weeks after they get sick.

And, lately, those arriving, whether delivered by ambulance or private vehicle, seem to be sicker than they were before the holidays.

“Poor blood pressure, respiratory issues, sepsis, we’ve seen a lot of strokes this month,” Paradis said.

A new one, she added, is an increase in reports of people who are brought to the hospital after becoming unconscious and have to be revived through CPR. Once brought in for observation, many test positive for the coronavirus.

At Sharp Grossmont Hospital on Thursday nurses care for a patient diagnosed with COVID-19.

(Nelvin C. Cepeda / The San Diego Union-Tribune)

Full or near-full intensive care beds have kept more patients in the ER for longer than was previously the case.

“We are an ICU at certain parts of the day,” Larimore said. “We’ll hold six, eight, maybe 11 ICU (patients) down here until there is room,”

Though it is licensed for 524 beds, Grossmont’s adult capacity tends to be closer to 420 or 430. In recent weeks, as demand for intensive care beds has increased but staffing has remained relatively stable, administrators have begun pulling nurses from other units and asking them to work as “extenders” alongside ICU nurses who are assigned three patients rather than the usual two.

Lindsey Dittmar, a critical care nurse who has been working with two extenders, said the extra help has made the increasing load bearable. But nothing can truly correct for the experience of working 10 straight months in an intensive care unit where no visitors are allowed.

Day after day, week after week, month after month she has had to watch some patients die without really getting to say proper goodbyes to their families. Even when family members are allowed to come to the bedside for 20-minute final goodbye visits, witnessing so much compressed grief just builds up, especially because her husband is also an intensive care nurse.

It is important, she said, not to try to keep that level of emotional strain bottled up.

“He cried last night, and I cried the week before,” Dittmar said. “We just see a lot of really sad things. It’s OK to feel overwhelmed just as long as we allow ourselves to feel it and express it to each other.”

Of course, expressing those frustrations, and trying to tell the public what they’re seeing through social media, can bring its own secondary level of trauma as many in the public have begun calling nurses who were revered in the spring and summer liars and profiteers.

Dennel Wildey, who works on a medical and surgical floor with 27 beds that has been filled with COVID-19 patients since May, said that backlash has been discouraging, especially when doing her job, even just delivering dinner to her patients, requires suiting up in layers of protective equipment.

Nurses put on new gloves and gowns and wear a PAPR, powered air purifying respirator, before entering a room with patient who has COVID-19.

(Nelvin C. Cepeda / The San Diego Union-Tribune)

“Sometimes it just feels like all of this work we’re doing is for nothing,” she said. “Everybody just keeps getting COVID.”

It’s a feeling, she said, that loses to her own internal conviction that being a nurse is her true calling.

Grossmont, and its sister hospitals across the region and across the nation, have done what they can to convert beds and staff to meet the demand. That includes an orthopedic unit at the hospital that has flipped back and forth from orthopedic surgery to COVID-19 care with each spike in caseload.

Leah Karnya said she wishes that more people could understand the risk they’re taking when they forgo masks and gather for holiday parties. What they say about one’s chances of dying or ending up in a hospital bed after becoming infected is true. Most recover without need for significant medical attention. More should realize, she said, that no one is really certain exactly what future problems will come with a novel coronavirus infection.

“What are the life-long effects? What about blood clots? What about stroke?” she said. “Do you really wanna risk it? I don’t.”

"many" - Google News

December 20, 2020 at 09:02AM

https://ift.tt/3rd119N

COVID-19 crushing county's ERs: Too many patients, too few beds, not enough staff - The San Diego Union-Tribune

"many" - Google News

https://ift.tt/2OYUfnl

https://ift.tt/3f9EULr

No comments:

Post a Comment